by Ralph Brauer | 7/01/2009 11:03:00 PM

Not long ago I found a disconcerting message on my answering machine. It said simply, "Don't send me any more emails. We went bankrupt." It is a message that has been reverberating through towns in America mostly below the radar screen of the mainstream media.

The businesses filing for bankruptcy range from manufacturers to auto dealers. Some of them are national, many of them are regional, and quite a few are local, the anchors of many small towns. A lot of them are niche businesses. By that I mean they operate in specialized markets often as suppliers to larger firms.

How Bad Is It?

The increase in bankruptcies has skyrocketed in the past year. Despite all the optimistic reports about this economic crisis having turned the corner, that is not the case when it comes to bankruptcy. Last year recorded the highest number ever since the law was changed in 2005 and this year will probably exceed that. Currently we are experiencing a daily filing rate of over 5,000!

As usual a graph tells the story:

Note the precipitous climb of the graph from a little over a thousand a day in 2006 to over five times that many per day in less than two years!

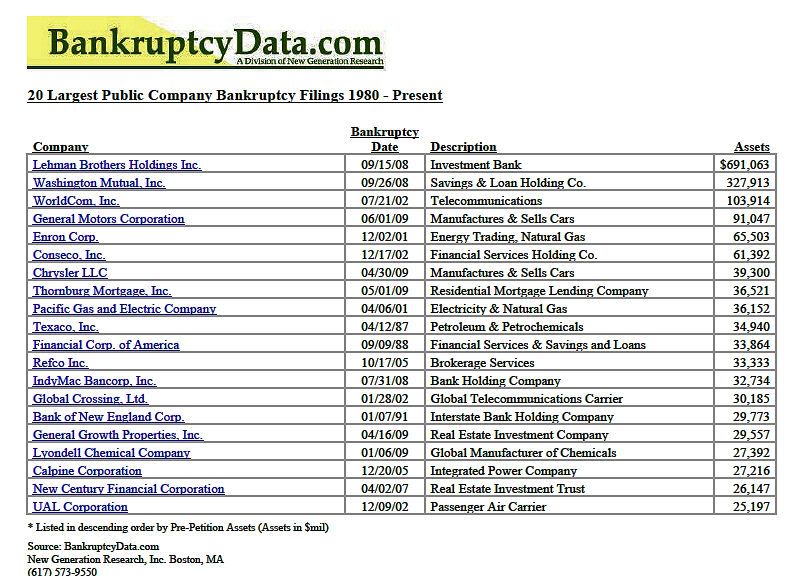

But it is not just the number of bankruptcies that is disconcerting but the size of them. A chart of the largest bankruptcies from 1980 until the present reveals that most of them have occurred in the last few years--the latest and most notorious being General Motors.

To put this in a soundbite, notice that of the top ten, five have occurred in the last year.

While it is difficult to compare total bankruptcies in the current crisis with those during the Great Depression because of changes in the bankruptcy laws along with monumental social changes (in the 1930s significantly more people lived in rural America making a living as farmers), the size issue does point towards an important and unsettling difference between our own times and the 1930s.

This crisis is notable in that not even during the Great Depression were such large and important corporations forced into bankruptcy proceedings. A glance at this list shows today's crisis has hit multiple sections of our economy including auto manufacturing (two of the so-called Big Three), finance, telecommunications, energy, and transportation. Only two of these failures--Enron and World Com--are directly attributable to criminal corporate malfeasance.

In a paper on bankruptcy during the Great Depression authors Bradley and Nary Hansen point out:

As a proxy for unemployment among wage earners, we use the bankruptcy rate among manufacturers. We expect a positive correlation between manufacturing bankruptcies and wage earner bankruptcies.

The Hansens found that positive correlation in their examination of data from the Great Depression which suggests that the other shoe has yet to drop in terms of the impact of thus depression.

The Statistics

The definitive bankruptcy statistics come from the place where bankruptcies end up--the U.S. Courts. Their June 28 report contained a chart that tells the story:

Note the dramatic increase in business bankruptcies over the last year--61%.Think about this statistic for a minute. It tells us that in the last year almost 50,000 businesses went under, which means an average of 1,000 per state. If you use the Census Bureau statistic of an average of 16 employees per business that would mean 16,000 people per state and 800,000 nationally no longer have a place to work.

The problem with these data is that according to an influential paper by Robert Lawless and Elizabeth Warren, they dramatically undercount the percentage and number of business bankruptcies. The two point out:

Based on new research from the Consumer Bankruptcy Project, if historical measures were used, we estimate as many as 17.4% of all current bankruptcy filings involve the failure of a business. Extrapolating to all filings, we estimate that rather than the 37,000 business filings reported by the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts (AO) for 2003, there were between 260,000 and 315,000 bankruptcies that historically would have been counted as business filings but that in 2003 were not

If we extrapolate these findings to this past year that means the number of business bankruptcies would have been in the hundreds of thousands, rather than a "mere" 50,000. Lawless and Warren point out the implications of this for public policy which:

Has set the stage for legislators and policymakers to recast bankrupt debtors from unfortunates caught up in the caprices of unforgiving market changes to overspenders responsible for their own misfortunes.

If you are a systems thinker you realize that this unemployment and bankruptcy will reverberate through the economy. The companies that went under will no longer pay taxes in their communities, lowering the tax base. The companies that they purchased supplies and materials from will have to find other customers. The communities in which these businesses once were important institutions now must somehow find other businesses to replace those they lost. In this economic climate that is a daunting task, which will inevitably lead communities to bend over backwards to attract these replacements, further increasing the property tax burden on those very same homeowners caught in the subprime crisis.

Meanwhile those who are unemployed will have to find other work or collect unemployment. It is doubtful many of them will find work at the same salary that they enjoyed before, so their purchasing power will decline and some of them will default on mortgage, car or credit card payments.

For corporations bankruptcy is essentially a credit crunch. Corporations file for Chapter 11 or Chapter 7 because their debt has increased to the point where their creditors call in their loans. It is the corporate equivalent of the mortgage crisis and like the mortgage crisis sorting out who is at fault becomes a critical policy issue. Is there an equivalent to the subprime scandal in the rash of corporate bankruptcies? Is there a legislative action parallel to the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Banking Act that played a role in the crisis?

There seems little question, if any, from a business point of view, that in response to the current crisis creditors have tightened their lending practices. As financial institutions have faced their own potential demise, they have called in their loans to stay afloat. Bankruptcies, like mortgage foreclosures, are a manifestation of an economic collapse.

Bankruptcy Law

Bankruptcy law is a formidable thicket of definitions and procedures that requires a special personality who not only knows all the nuances of the law but who also is part psychologist. Chapter 11 aims to restructure a company so it can continue to function. If all goes according to the plan filed with the bankruptcy judge, when the bankrupt company's obligations are discharged it can emerge from the process as a survivor who has lived through some tough times.

Chapter 11 requires attorneys to apply some tough love to clients who sometimes land in court because of profligate spending, questionable decision-making and incompetent management. Like someone working with an addict or alcoholic you have to get a client to see the error of their ways while convincing them to undergo and stick to a treatment program that is emotionally, physically and psychologically daunting.

On the other hand for Chapter 7, which is essentially the complete liquidation of a company, the task is more for akin to that of a funeral director who must oversee the burial of companies that suffered the equivalent of a fatal accident or terminal illness. Unlike Chapter 11, Chapter 7 is The End with all the suffering and grief that entails.

Sharp legal minds will recognize that for businesses bankruptcy is exactly the opposite as it is for consumers. For individuals Chapter 7 once was a good way to escape from under burdensome debt. People could declare bankruptcy and walk away from whatever debts they had. College students, for example, could use bankruptcy as a way of liquidating all their student loans. Credit card addicts use it as a way of wiping clean sometimes profligate spending. On the other hand, for businesses Chapter 11 was preferable to Chapter 7 because it at least allowed them to restructure and continue operating.

All that changed with the 2005 revision to the bankruptcy code, which received a great deal of attention for making it more difficult for individuals to file for Chapter 7. It is important to note the changes enacted in 2005 were driven by creditors, which is why the debate over its passage was sometimes bitter and controversial.

Less well known are the changes the 2005 law made in business bankruptcies. In a paper on the 2005 law in the Southern Illinois University Law Journal, Robert Lawless stated its impact on small business in no uncertain terms, arguing that changes in small business bankruptcy in the 2005 law:

Are unprecedented developments in American law. Never before has Congress singled out small businesses for harsher treatment than large corporations.

Lawless' paper is an excellent discussion of the major changes in the law, changes that slipped under the radar screen of most Americans. First, the law defined a small business as any firm with more than $2,000,000 in noncontingent liquidated secured and unsecured debt. As Lawless points out:

Empirical studies of business bankruptcies suggest this definition will cover most business filers.

What the law did to small businesses is one of the best-kept secrets of this entire economic crisis, with virtually no one in the press even calling attention to it. Because it is written for lawyers and scholars, Lawless' article can be daunting, but it certainly should be required reading for anyone researching the current crisis. Among its key findings:

- A small business debtor loses the protection of the automatic stay (1) if it is a debtor in a pending small business case, (2) if it was a debtor in a small business case that was dismissed in the previous two years, or (3) if it was a debtor in a small business case that was confirmed in the previous two years.

- By denying the automatic stay only to small businesses filing a second chapter 11, Congress expressed hostility to small businesses reorganization alone.

- The expanded reporting requirements are onerous and many are unnecessary.

- What makes the expanded disclosure requirements perhaps most worrisome is that each becomes grounds to seek possible dismissal of a chapter 11 case.

- Together, the new disclosure provisions and the tighter dismissal rules make chapter 11 much more hostile to reorganizing small businesses than the pre-2005 law.

- We can expect entrepreneurial activity in the United States to decline.

In essence Lawless tells us that in the midst of the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression, a majority of American businesses are frantically trying to keep from drowning with the weighty anchor of the 2005 bankruptcy law changes tied to their waists. It has also pushed more businesses into Chapter 7.

Curiously this was predicted back in 2002 when Baird and Rasmussen wrote about the impending demise of Chapter 11:

To the extent we understand the law of corporate reorganizations as providing a collective forum in which creditors and their common debtor fashion a future for a firm that would otherwise be torn apart by financial distress, we may safely conclude that its era has come to an end.

The Real Estate Shell Game and the Demise of Circuit City

After allowing financial institutions to engage in all sorts of shenanigans that helped to bring about the mortgage crisis and today's economic woes by repealing the Glass-Steagall Act in 1999, Congress and the Bush Administration proceeded to bestow another gift on financial institutions with a little-known addition to the 2005 bankruptcy law rewrite. Among those pushing for the changes was Citi, the same firm that played a huge role in the repeal of Glass-Steagall.

In the new economic world created by the repeal of Glass-Steagall, Citi, the company that began as a loan-sharking business, was now heavily involved in the credit card business, so it had two reasons to push for the 2005 changes. Most of us know about the changes in credit card debt, but few know that the law essentially limits the ability of businesses to restructure real estate debt. Of course, this hits retailers especially hard because most of them rent space or are paying off the costs of building new stores.

If you wonder why so many stores in suburban malls now lie empty and why big box retailers such as Circuit City have gone under you need only read the following paragraph from testimony delivered last October to the House Subcommittee on Commercial and Administrative Law by Professor Jay Westbrook of the University of Texas Law School, Professor Barry Adler of the New York University School of Law and Lawrence Gottlieb, the Chair of the Bankruptcy & Restructuring Group at Cooley Godward Kronish LLP.

[The 2005 Law] has left retailers without adequate time and money to effectuate operational initiatives and cost cutting measures needed to resuscitate their businesses. Retailers now enter the Chapter 11 arena with little choice but to narrowly tailor their strategy to ensure that their lenders are not deprived of the substantial benefits and protections conferred by section 363(b) of the Bankruptcy Code, which authorizes the use, sale or lease of estate property outside the ordinary course of business upon court approval.

BAPCPA’s constrictive liquidity provisions and the enormous leverage handed to secured lenders as a result thereof have eliminated the ability of retailers to control the Chapter 11 process as a “debtor-in-possession.” Rather, the process is now controlled almost exclusively by prepetition lenders, who have essentially assumed the role of "creditor-in-possession."

What this means is that real estate debt now is one of the "first in line" when a company gets in financial trouble. This helps to explain why the demise of companies like Circuit City came on the heels of the mortgage crisis, for their financial difficulties constituted a kind of retail business mortgage crisis.

Bankruptcy attorney Lawrence Gottlieb testified:

Today, retailers almost invariably begin the Chapter 11 process with little hope of emergence. Numerous economic factors – the credit crunch, the subprime lending crisis, the slowdown of the housing market and eroding value of retail commercial leases – have clearly contributed to this downward spiral.

Data confirm his fears:

Since the enactment of BAPCPA in late 2005, no more than two retailers have successfully emerged from Chapter 11 as reorganized entities.

With this in mind it puts the May retail statistics in some perspective. The press widely reported that May was the first time in three months that retail sales rose--this time by a paltry .5%. Reports attributed this to auto dealers steeply discounting prices for new cars to try to deal with the bankruptcy of General Motors, the lower price of gasoline and the impact of federal stimulus funds.

Yet behind these seemingly optimistic reports lay some grim realities:

The International Council of Shopping Centers last week said May same-store sales dropped 4.6 percent from the same month last year, more than double its forecast of a 2 percent decline. Macy’s Inc., Dillard’s Inc. and Saks Inc. were among merchants that reported steeper declines than analysts estimated as Americans focused on buying essentials rather than discretionary items.

Note that the names of some of these retailers routinely pop up in discussions of who will be the next big retail firm to go under.

The Opposition

While he was still alive, the last politician who proudly wore the label liberal--Minnesota Senator Paul Wellstone-- almost single-handedly fought off these changes, according to the PIRG Bankruptcy Campaign. In much the same way John Quincy Adams used the rules of the House to argue against slavery, Wellstone used the rules of the Senate to throw roadblocks in front of attempts to rewrite American's bankruptcy laws. Wellstone's objections have a certain prophetic quality about them, for he seemed to sense the economic storm that was brewing on the horizon.

In his book, The Conscience of a Liberal, (which is probably the last book in which a politician openly claimed that title), Wellstone wrote about why he opposed attempts to change the bankruptcy laws.

The vast majority of bankruptcies were caused by major medical bills, loss of job, or divorce. Current bankruptcy law was a major safety net for the middle class in America.

In a letter to then Majority Leader Trent Lott detailing his opposition he stated:

I continue to be puzzled by the false urgency for this bill. As bankruptcy rates fell steadily in the past two years, the rhetoric about the "crisis" in filings became even more shrill. But even more perversely, projected increases in bankruptcy filings for the coming year – as a result of layoffs and falling income due to a cooling economy – is now being used to justify rolling back the bankruptcy safety net. In other words, now that more working Americans will be forced to file for bankruptcy because of circumstances beyond their control, we should make it harder for them to do so. I for one will have difficulty making that argument to the newly unemployed steelworkers in my state.

Unfortunately for businesses and consumers, Paul Wellstone died before the passage of the 2005 law. It is one of history's great ifs whether that bill would have emerged from the Hill in its present form.

Instead in the Senate eighteen Democrats and one Independent voted with 55 Republicans to change the law. Only 25 Democrats voted no. Among them were Barack Obama, Charles Schumer, and Chris Dodd. Hilary Clinton was not present for the vote because her husband was undergoing open heart surgery. Joe Biden voted in favor if it as did John McCain and current majority leader Harry Reid.

The Big Picture

The repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act allowed banks and other financial institutions to engage in the shenanigans that helped to cause this crisis. The 2005 bankruptcy law changes, which were also a gift to those financial institutions, now make it more difficult for financially strapped businesses to reorganize.

It doesn't take a Harvard economist to envision the scenario. Banks get out of control after the repeal of Glass-Steagall. To stave off financial collapse they start calling in loans. The 2005 law makes it more difficult for businesses to restructure that debt. The result: a thousand bankruptcies per state in the last year. But because of the law these are not your usual bankruptcies. The new law pushes more firms into Chapter 7.

I know just such a business. It had been in the same family for three generations, having survived the Great Depression in part because one generation essentially defied New Deal regulations. The company did not manufacture anything that would have benefited from World War II, yet it found a way to land a few key contracts. After the war it prospered along with the rest of the country. The company continued to survive because of the high quality of its products and the loyalty of its customers, but it found itself trying to compete in a market that had become dominated by a few giant corporations.

The town where this business was located could be any rural Midwestern city with plowed fields extending right to the city limits. In the summer you can see the corn stalks waving in the breeze and hear the cries of pheasants from between the rows. In this flat landscape the horizon seems to extend forever, promising endless possibility and a limitless future. The heart of Main Street still consists of brick buildings with ornate stone façades sporting dates that hearken back to the 19th century carved into imposing gray granite blocks

Many of the businesses located behind the glass display windows that look out onto the wide streets are as old as the buildings themselves, having been in the same family for over a century. These people are survivors, for they weathered the dust clouds and stark realities of the Great Depression without ever closing their doors. For people living in these towns, these old family business provide a solid foundation as massive as the stones that were used to build those stores.

These businesses are literally the heart and soul of these towns so when one of them fails it is not only the death of a business but a loss felt keenly by everyone living in those towns as keenly as if someone in their families had died. In these towns an empty storefront on Main Street stares back like a grim tombstone reminding all of their community's mortality.

Clearly this business and the others that have failed testify that we do not yet truly understand the full dimensions of what this country faces. However there is a cultural and historical parallel that most analysts have overlooked.

A Parallel

In terms of large-scale corporate bankruptcies the closer parallel to our time is the so-called Long Depression that covered the last three decades of the nineteenth century, encompassing the famous 1893 Depression. An article from the New York Times during those years sounds eerily familiar:

The year 1893 began in doubt and ended in disaster…Its opening found the financial community in a state of serious concern about the currency issue…Banks began to be rapidly drawn upon; contraction of loans followed; and then came the panic…The whole country seemed to be calling on New York for money…How far the decline will go, or how long it will continue, it is no use to try to guess. [December 31, 1893]

The article named the firms that had already gone down like a bell tolling the dead: National Cordage, the Reading Railroad, the Union Pacific and Great Northern. For the nineteenth century the railroads meant as much to the economy as automakers meant to the twentieth, so the parallels extend even deeper.

A second parallel is the degree of corporate concentration. In Democracy in Desperation, a history of the 1890s Depression, Douglas Steeples and David Whitten observed:

Nowhere was consolidation more rampant than in the railroad industry…By the early 1890s, the Pennsylvania, Reading, Santa Fe, Great Northern and New York Central; the Union, the Southern, and the Northern Pacific; and a few others controlled thousands of miles of track and millions in capital each. [p. 19]

A Cultural Implosion

The Long Depression of the last half of the 19th century was above all a cultural phenomenon in which America's economic, social, and political arenas simultaneously underwent a fundamental shift in values. The nation experienced a change in its collective mindset as profound as the one which led their ancestors to sever their ties with Great Britain. Historians have labeled this shift as a transition from a rural to an industrial society.

But it involved far more than merely changing the way the nation did business. No institution, no community, no individual was immune to the change. It altered everything that they did from the way they built their houses and raised their crops to the ways they schooled their children. In a famous 1855 painting The Lackawanna Valley, artist George Inness captured that shift in a single image. It shows a massive smoke- belching locomotive traveling across the pristine rural landscape of the Hudson River Valley.

Note still standing amidst the stumps remains scraggly tree visually blocking the path of the train that has emerged from the smoking roundhouse dominating the desert-like background.

Were I to be forced to select a single contemporary cultural document that forms the equivalent of that painting I would choose the Matrix movies with their stark vision of a future in which the differences between humans and robots have evaporated and all is under the control of a single massive computer.

Today the changes of the late 19th century are seen as historically inevitable. But to the people of those times, they were far from that. In fact opposition to the most dramatic of these changes in the form of the Progressive and Populist movements helped to lessen their more dramatic impacts and laid the groundwork for what I term the Second American Revolution in which this nation found a way to maintain its democratic commitment to the level playing field in the face of industrialization.

Today this economic crisis and asks whether we can maintain that principle as we confront the massive changes our society is undergoing. Whether we can create the equivalents of the Progressive and Populist movements of a century ago may well determine whether our society survives. Paul Wellstone believed that America had in its soul the ability to weather this crisis. Let us hope that he was correct.

I remember the debate about the bankruptcy bill. What I can't figure out is whether the current crisis qualifies as an unintended consequence....