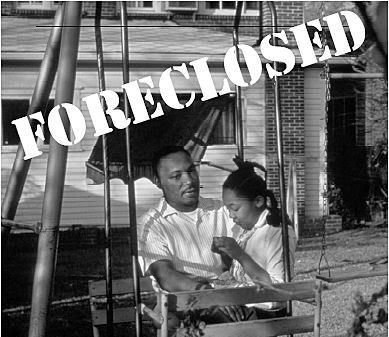

Photo: United for a Fair Economy The State of the Dream

Part II of IV

Sandy Weill's story tells how racially-biased predatory lending lies at the center of the economic crisis. A third-generation American, Weill grew up on the streets of Brooklyn where for some the road to success was a place whose name came from a structure built to protect the city from Indians, pirates and other invaders and whose die was cast when a small group of men met in secret under a buttonwood tree: Wall Street.

Like the hero of a Horatio Alger tale, Weill began his climb to success not in the proverbial mail room but as a $35 a week clerk, eventually clawing his way to become second-in-command at American Express. But Weill had an itch for more so he cashed in his chips and set about looking for his own business. In 1986 he settled on a Baltimore loan company named Commercial Credit that specialized in predatory lending.

The tale of how Weill would use Commercial to build the financial empire that became Citigroup is the story of the financial crisis and at the heart of that story is racial discrimination and predatory lending. In short, predatory lending made Citi into one of the nation's largest financial institutions and now is responsible for its downfall.

The Beginnings of Citi

If Weill did any due diligence at all, he knew quite well he was buying a company whose entire existence was predicated on ripping off people of color. Commercial already had a shady reputation when Weill moved in on it. In 1973 the FTC had issued an order demanding Commercial cease using deceptive and hardball tactics to entrap those in search of a loan. In his article “Banking on Misery Citigroup, Wall Street, and the Fleecing of the South,” Michael Hudson relates that Weill's assistant, Alison Falls, was appalled at the idea of buying Commercial:

Hey guys, this is the loan-sharking business. "Consumer finance" is just a nice way to describe it.

After Weill bought the company did he seek to curb these practices? Quite the contrary, Commercial became even more aggressive. After all, Weill's whole business plan was predicated on using Commercial to launch a larger company and in order to do that he had to get as much as he could out of Commercial, which meant squeezing clients even more.

Some of Weill's former employees tell stories of being pressured into steering clients into dubious deals. Hudson quotes Sherry Roller vanden Aardweg, who worked for Commercial in Louisiana from 1988 to 1995. She agrees there was “a tremendous amount of pressure” to sell insurance: That insurance was issued by another Weill acquisition American Health & Life.

We kept adding insurance that we could offer. It just kept growing. It was beginning to get a little bit ridiculous.

Frank Smith, who worked for Weill in Mississippi, put a perspective on ripoffs such as "closed folder closings" in which documents adding to the cost of the mortgage were kept from the client:

They need the money or by God they wouldn’t be at the finance company. They’d be at a bank.

Weill used the money milked from Commercial's clients to acquire insurance and finance company Primerica. In 1990 he acquired Barclay's Bank. Meanwhile the stories told by African Americans victimized by Weill certainly sound like loansharking. Two Mississippi clients of Commercial signed on for Annual Percentage Rates (APR) of 40.92 and 44.14. Another client paid $1,439 for insurance on a $4,500 loan.

Ripoffs like this attracted the attention of attorneys and law enforcement officials, especially in the South, where Commercial had a large presence. Hudson reports:

In 1999, the company agreed to pay as much as $2 million to settle a lawsuit accusing Commercial and American Health & Life of overcharging tens of thousands of Alabamans on insurance.

Jackson, Miss., attorney Chris Coffer says he obtained confidential settlements for about 800 clients with claims against Commercial Credit or its successor, CitiFinancial.

In 1999, the company agreed to pay as much as $2 million to settle a lawsuit accusing Commercial and American Health & Life of overcharging tens of thousands of Alabamans on insurance.

How much money African Americans probably overpaid Commercial can be glimpsed from one study by the Community Reinvestment Association of North Carolina. Testifying before a 2006 hearing of the Federal Reserve in Atlanta, CRA-NC Community Organizer Richard Brown cited the findings of the study, Paying More and Getting Less: An Analysis of 2004 Mortgage Lending in North Carolina:

Our key finding is that disproportionately, by a ratio of more than 4 to 1, African Americans pay more interest on home loans than whites do in North Carolina.

Cultural Impacts

Like some modern plantation, subprime lending was built on the enslavement of African Americans, only instead of being field hands or sharecroppers their lives were indentured to loan sharks. Like the infamous overseers who ruled plantation life with the crack of a whip, the loan sharks ruled the lives of African Americans with whips woven together with words the way real whips are woven from strips of leather. While these words might not have inflicted the physical wounds overseers specialized in, the mental scars inflicted by the words woven into loansharking mortgages were socially and psychologically devastating.

Like slavery, loan sharking helped to turn the African American family into a hot-button issue whose implications are still the subject of volatile debates within and outside the community. Yet while the particular sociological and cultural impacts of loansharking may be the subject of some debate, there is agreement about the big picture: the impact rippled through families and communities like a rogue wave bringing misery and destruction. In the inner city and some rural communities, especially in the South, African American families faced two equally devastating choices when it came to housing: deal with the loan sharks or deal with the slum lords.

Loan sharking also rippled through American culture. Call it apartheid or something else, whatever label you assign to it the forced separation of whites and people of color is the number one issue of post World War II America. As surely as South Africa carved out "homelands" for its black citizens, so FHA and others carved out the equivalent through redlining.

In the South African Americans and whites lived together but interacted through the elaborate codes and rituals of Jim Crow, but in the North the races were physically separated so a white suburbanite could grow up without having much association with people of color. As a result, while white Southerners saw African Americans as inferior, white Northerners saw them as abstractions.

The 90s Boom in Subprime Loans

Meanwhile Sandy Weill continued building Citi through mergers and acquisitions. In 1993 came the controversial merger with Travelers followed four years later by Citi's acquisition of Salomon Brothers. At the same Weill was building Citi, the mortgage market was undergoing some dramatic changes. Researchers began identifying a huge spike in the number of subprime loans. Loansharking had come from back streets and low budget store fronts to the center of America's financial empire: Wall Street.

A graph from the Woodstock Institute tells the Story:

This graph raises two obvious questions: what was fueling the growth and who was providing those new subprime mortgages? The first is still the subject of some debate among economists and others. For example, some have tied it to an increase in interest rates. In its explanation accompanying the graph Woodstock states:

Despite increasing rates in 1994, 1995, and 1997, however, subprime lenders continued to increase their refinance volumes. This suggests that subprime refinancings are not driven by homeowners refinancing to save money during times of declining rates and that subprime lenders are aggressively marketing loans regardless of the rate environment.

In part, the growth of predatory activity stems directly from the development of an increasingly specialized and segmented mortgage market, especially for refinance and home equity loans.

What was in it for others is the same thing that was in it for Sandy Weill--profits. Forbes reported that in the boom of the 90s, subprime companies enjoyed returns up to six times greater than those of the best-run banks.

United for a Fair Economy put it more bluntly:

The subprime lending crisis has occurred because a financial product intended for limited use by a limited number of people has been parlayed into another ill-fated bubble by some mortgage lenders lacking in integrity, foresight, and any vestige of civic concern.

What made this possible was the packaging and trading of loans which goes under the fancy name of securitization. A Federal Deposit Insurance Company report describes how this process works:

Thirty years ago, if you got a mortgage from a bank, it was very likely that the bank would keep the loan on its balance sheet until the loan was repaid. That is no longer true. Today, the party that you deal with in order to get the loan (the originator) is highly likely to sell the loan to a third party. The third party can be Ginnie Mae, a government agency; Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac, which are government sponsored entities (GSEs); or a private sector financial institution. The third party often then packages your mortgage with others and sells the payment rights to investors. This may not be the final stop for your mortgage. Some of the investors may use their payment rights to your mortgage to back other securities they issue. This can continue for additional steps.

As usual a graph tells the story of the growth of these new investment vehicles.

The FDIC goes on to explain how various pooling tactics package subprime loans, taking you into a thicket of acronyms like (MBSs), collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), and structured investment vehicles (SIVs)--all essentially are ways of spreading the risk of pooled mortgages. Notice that the initial upswing in MBS begins in the late 1980s. That was due to the tax reform act of 1986.

Ginnie Mae (Government National Mortgage Association) and Freddie Mac (Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation) had been involved with MBS before the 1986 bill, but the Reagan Administration's gift to the home mortgage industry introduced another acronym into the mix: REMIC--Real Estate Mortgage Investment Conduit, which is yet another tool for pooling and packaging mortgages. None other than Freddie Mac described the importance of the 1986 bill:

The REMIC law was passed as part of the Tax Reform Act of 1986 and marked the beginning of the growth of the CMO [Collateralized Mortgage Obligation] market.

Once financial institutions began to catch on to this and entered the thicket of securitization in a big way, there was no turning back. The American economy would never be the same. Put the two graphs above together and you have the story: the initial growth of the subprime market was enabled by the growth in MBS. There remained only one regulatory hurdle in place, one that had been there since the Great Depression.

The Repeal of Glass-Steagall

Had Carter Glass been alive in the 1990s it is doubtful any of this would have happened, but by the time he put his name on the Glass-Steagall Act during the Depression, Carter Glass was an old man. He had actually been a delegate to the 1896 Democratic National Convention when William Jennings Bryan gave his "Cross of Gold" speech and most of his political life he had a Bryan streak in him that included a distaste for banks. When he left Woodrow Wilson's cabinet at the end of Wilson's term he was already warning of the dangers of uncontrolled banking, particularly banks getting involved in the stock market and other financial dealings.

Carter Glass would not have liked Citi or Sandy Weill. Weill, in turn, had little use for what Glass had created, seeing it as an obstacle that stood in the way of his fulfilling his vision of the kind of "full-service" banking Carter Glass had feared.

The Glass-Steagall Act was designed to keep banks out of the securities business because Carter Glass and New Deal officials including President Franklin Roosevelt believed that one of the causes of the Depression was that banks had strayed too far from their original functions during the 1920s. According to a paper by Jill M. Hendrickson:

in 1932, 36 percent of national bank profits came from their investment affiliates (Wall Street Journal 1933, p. 1).

Glass-Steagall built a wall between banking and other financial services and the ink on the paper was barely dry when the bankers and their allies in the Republican Party began howling. Over the next half century there were numerous attempts to weaken or scuttle Glass-Steagall, but in the midst of the securitization boom the cries to tear down the wall of Glass-Steagall grew louder. In 1990, the Fed, under former J.P. Morgan director Alan Greenspan, permitted guess who--J.P. Morgan--to become the first bank allowed to underwrite securities.

It would be none other than Sandy Weill who would put in motion the forces that ended Glass-Steagall when he essentially gave the federal government the equivalent of an upraised finger by proposing the most audacious financial merger in American history: he would merge one of the largest insurance companies (Travelers), one of the largest investment banks (Salomon Smith Barney), and the largest commercial banks (Citibank) in America. The problem was the merger was illegal in terms of Glass-Steagall.

Weill convinced Greenspan, Robert Rubin and President Bill Clinton to sign off on a merger that was illegal at the time, with the expectation that Congress would repeal Glass-Steagall. That would happen with a big push from Sandy Weill. First, he spent over $200 million in lobbying fees to convince Congress to go along with his merger. It still ranks as the largest single amount spent by one firm on one bill over the shortest period of time in American history.

When the conference committee charged with reconciling the House and Senate versions of the repeal bill seemed stalemated, it was Sandy Weill who applied the final push needed to get the bill passed. Here is the now oft-quoted Frontline report of what happened:

On Oct. 21, with the House-Senate conference committee deadlocked after marathon negotiations, the main sticking point is partisan bickering over the bill's effect on the Community Reinvestment Act, which sets rules for lending to poor communities. Sandy Weill calls President Clinton in the evening to try to break the deadlock after Senator Phil Gramm, chairman of the Banking Committee, warned Citigroup lobbyist Roger Levy that Weill has to get White House moving on the bill or he would shut down the House-Senate conference. Serious negotiations resume, and a deal is announced at 2:45 a.m. on Oct. 22. Whether Weill made any difference in precipitating a deal is unclear.

The Aftermath

With Glass-Steagall out of the way, Sandy Weill had his merger and the American financial industry now had a green light to enlarge on subprime lending. Some followed Weill's model of consolidating loan and insurance companies as he had done with American Health & Life and Travelers, taking loansharking to a level those who had engaged in it back when it was done in storefronts with peeling paint could have never imagined.

More money than any organized crime syndicate could have dreamed of flowed into the coffers of the subprime lenders. What had been an activity aimed mainly at people of color now became linked to complex financial instruments such as tranches and derivatives, that to an uninitiated mind resembled nothing so much as the old shell game. Where's the mortgage? Under this fund? No. guess again. Inner city and suburb which had been separated by redlining became linked by acronyms--MBS, CDOs, CMOs. But as we shall see in the next essay, ripping off people of color would continue.

Postscript: The Revelations of Language

Some reading this essay might object to my linking loansharking and subprime mortgages, but Sandy Weill from the streets of Brooklyn would get it. Subprime is perhaps one of the most misleading euphemisms ever devised, because it means exactly the opposite of what the term implies. The Investopedia offers a succinct definition:

A type of loan that is offered at a rate above prime to individuals who do not qualify for prime rate loans.

As for loansharking, a definitive definition is a little more difficult to come by. Investopedia says it is anyone who charges above the legal interest rate (which is set by some states). Several others add that it also involves an implied or real threat to injure the person who doesn't pay off. As if to throw a ringer into that definition there are dozens of references to "legal loan sharking." Perhaps the broadest definition is at Wiktionary:

Someone who lends money at exorbitant rates of interest.

These definitional niceties represent not merely semantic nit-picking, but in fact provide a vital piece to understanding the cultural shifts that have accompanied the economic crisis. One of the unspoken theses in this series of essays is that by clothing loansharking in the more respectable term of subprime, it suddenly made it not seem so bad to lend money to people--especially people of color--at higher rates. It is reminiscent of the semantic games segregationists used to play with strategies like the "literacy law." CNN even named "subprime" the word of the year. Can you see them doing that for loansharking?

In a fascinating article, Ben Zimmer explains how subprime came to have its present meaning, noting that the earliest use of the term was in industry to describe something below grade while in the 1970s banks used it to refer to loans below the market rate.

Something happened to the word in the 1990s, however. Now it was the borrowers themselves who were being classified as "less than prime" based on their shaky credit histories. [My underline]

Zimmer is on to something when he says the term was applied to people, because as we have seen, a high percentage of subprime loans were aimed at people of color. So the phrase about borrowers being "less than prime" has more meaning than Zimmer perhaps realized when he wrote that sentence.

At the same time that subprime underwent a shift in meaning it is quite clear that so, too, did loan sharking. The earlier references clearly have a criminal tinge to them. In old crime movies "loan sharking" was always thrown in with other nasty activities gangsters perpetrated on the innocent and not so innocent. Yet the recent references seem to take the gangster and the "enforcer" out of the term, so loan sharks just charge higher rates without threatening to break your legs or worse.

This linguistic convergence of loan sharking and subprime reflects an economic and social convergence, for it seems to date from about the time Sandy Weill first bought Commercial. So as Weill took what his own assistant termed a loan sharking operation to the pinnacle of corporate success, the financial industry adopted the euphemism of subprime just as it was getting into this type of lending.

In truth it is the financial industry itself which has helped to blur the distinction between conventional lending at a higher rate and the hardball, card-sharp techniques of the loan shark. That in turn has given rise to a new term "predatory lending" which has largely replaced loansharking in our vocabulary, creating a living for economists and others who write papers dissecting the differences between the two as if they mattered to those who have to pay exorbitant rates.

As we plunge deeper into the financial crisis, two things are clear: it takes a pretty good lawyer to decipher the standard mortgage agreement and an even better wordsmith to explain if an agreement charging more than the standard interest rate is an innocent subprime mortgage or predatory lending. For me I will continue to use loansharking with its connotations of shady activity until the financial industry cleans up its act.

Zimmer ends his article by observing:

Here's hoping that in the not-too-distant future we can look back on the current usage of subprime as a quaint artifact of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Twenty years ago the mainstream financial industry would have nothing to do with subprime lending. Now they are using language much like the defenses of the original loan sharks to defend it, talking about how they are performing a service for people who cannot get loans any other way.

In the next essay we will look at the consequences of the Glass-Steagall repeal, the fall of Sandy Weill and Citigroup, and the growth of so-called subprime lending. Then you can make up your own mind about whether to call it loansharking or continue to use that other euphemism.

Continue to Part III

Labels: Ralph Brauer

Ralph Brauer on 12/17/2008 4:40 PM:

Your comment is right on. One reason the racial nature of the housing problem has taken so long to surface is exactly the issue you describe--problems with sources. A second reason you also identify is the growth of corporate power and the difficulty in obtaining primary source materials about it. My former mentor, Joe Wall, who wrote biographies of both Carnegie and Dupont, used to speak about the problems of researching business leaders. There are a couple of biographies of Sandy Weill, but they are not of the caliber professional historians would accept.

I encourage you to continue your work and look forward to hearing more about it. If this series does nothing else I hope it encourages far better writers and researchers than I am to do exactly what you propose: something "done by lots of people on a large scale."

I am becoming more convinced that DuBois "color line" morphing into redlining after World War II may well be the most significant problem of the last half-century. It cries out for someone(s) to give it more justice than I have in these short pieces.

I have been making the argument, with my World History students and my colleagues, that corporate history -- or business history or whatever you want to call it -- is an important and neglected field of modern history. Both for the way it organizes our lives as participants and for the way it affects our options and life course as customers, the economic activities of businesses can no longer be viewed as solely economic activities, and can't be dealt with just in the aggregate and general.

Sources are going to be a real problem, but this series is the kind of thing that really needs to be done by lots of people on a large scale.