by Ralph Brauer | 10/17/2008 12:00:00 AM

By slow degrees the situation dawned on him that the banks had lent him, among others, some money--thousands of millions were--as bankruptcy--the same--for which he, among others, was responsible and of which he knew no more than they.Sound familiar? Does that describe your situation or that of someone you know trying to cope with the current economic crisis? Actually the somewhat-dated language and construction may be a give-away. Perhaps this comes from the Great Depression rather than from someone down the block or some op ed essay lamenting the mess we are in.

I doubt anyone reading that sentence, unless they were a very perceptive historian, could guess that it was written in 1893 in the depths of what most people consider the second-worst depression in American history. The author was one Henry Adams, son of Charles Francis, grandson of John Quincy and great-grandson of none other than the second President of the United States, John Adams.

Adams went on to write:

The more he saw of it, the less he understood it. He was quite sure nobody understood it much better...When Adams went to his bank to draw a hundred dollars of his own money on deposit, the cashier refused to let him have more than fifty, and Adams accepted the fifty without complaint because he was himself refusing to let the banks have some hundreds or thousands that belonged to them.

What Adams meant by that last statement was that he didn't want them to call in their loans or his mortgage--a situation that also sounds familiar.

The Wrong Depression and the Wrong Idea

I had already mostly written and had ready to post an essay on the bailout when the Dictator of the Treasury--as he was designated by law--made the unprecedented decision for the United States government to purchase shares in some of the nation's largest banks to transfuse some needed funds into what many see as desperate patient. Suddenly the essay needed a rewrite.

Meanwhile, the pundits were comparing the situation to 1932 and the Great Depression. They are dead wrong. They are looking at the wrong depression and as a result proposing the wrong solutions to the present crisis. If they analyzed Henry Adams' depression--the Depression of the 1890s--they might find a more enlightening perspective on our current troubles.

The 1890s Depression: The Data

One reason the pundits may be reluctant to look at the 1890s is that there is not much concrete data available to understand it since no one kept the voluminous figures that we do today about virtually every bank transaction. In fact I would take the radical position [more on this later] that we are so myopically focused on instantaneous data that we cannot see the forest for the trees.

In the 1890s they didn't even know how many people were unemployed. In Democracy in Desperation, a history of the 1890s Depression, Douglas Steeples and David Whitten demonstrate how wildly the estimates vary:

Most contemporary estimates of joblessness were for the winter of 1893-84, when exceptional distress attracted wide attention. Often of doubtful accuracy, they ranged upward from the estimate of Carlos Classon, Jr., in November of 1893 of a half-million. In December, Bradstreets proposed 0.8 million...The Knights of Labor and the American Federation of Labor asserted there were three million out of work as the new year opened. [p. 49]The problem with comparing these figures to those of the Great Depression is that that in the 1890s no one even knew how many workers existed.

In his book From the Founding of the American Federation of Labor to the Emergence of American Imperialism, Philip Foner estimates that three million out of a labor force of five million were unemployed--which would be a figure double the percentages recorded for the Great Depression. [p. 235]

Trying to get a statistical handle on the impact of the 1890s Depression, Steeples and Whitten report an 18% fall in farm income, a decline of 24% in manufacturing investment, a drop in freight car orders of 75%, and a precipitous fall in new stock issues of 63%.

The 1890s Depression: The Reality

Historian Page Smith, in what may well be the last monumental multi-volume history of the United States written by a professional historian, has written:

If we accept 1861 and the beginning of the Civil War, the year 1893 was the most dramatic in our history. [Vol. VI, p. 506]In The American Mind, Henry Steele Commager observed:

The decade of the nineties marked the end of an era; it heralded, even more unmistakably, the beginning of a new one...It fixed the pattern to which Americans of the next two generations were to conform, set the problems they were required to solve...To the American of the 1950s, the political figures of the nineties seemed almost contemporary. [p. 53]If some historians recognize the 1890s as a watershed, certainly the people living through those years, whether someone with the distinguished lineage of Henry Adams or one of the coal miners Stephen Crane wrote about in an essay where he journeyed 1,600 feet beneath the surface to find two miners with oil lamps toiling away in the darkness, all felt they lived in tumultuous times. In terms of economic, social and civil strife the 1890s make the Great Depression seem mild.

The 1890s Depression--The Rise of the Trusts

Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century the industrial world went about inventing itself, grinding everything in its path like some advancing glacier the spelled the end of one age and the beginning of another. Henry Steele Commager evoked the glacial metaphor as he described the rise of corporate power:

Before the glacier-like advance of the great corporation, small businessmen and shopkeepers were ground out of existence or absorbed. [p. 53]As business organized itself to stay competitive, three parallel developments took place. First, as Henry Adams' brother Brooks would recognize:

Throughout the ages it had been the favorite device of the creditor class first to work a contraction of the currency, which bankrupted the debtors, and then to cause inflation which created a rise when they sold property which they impounded.Brooks Adams recognized that a contraction by which fewer and fewer firms came to dominate the economy represented the major feature of his era.

In late nineteenth century America this took three forms. First there were the vast trusts which essentially were collusion agreements between producers to pool their resources and control the market. Nabisco, which at that time was called the National Biscuit Company, controlled 90% of the crackers sold in America. Trusts were formed by the salt, sugar, paint, cordage and wallpaper industries.

Steeples and Whitten report:

Nowhere was consolidation more rampant than in the railroad industry...By the early 1890s, the Pennsylvania, Reading, Santa Fe, Great Northern and New York Central; the Union, the Southern, and the Northern Pacific; and a few others controlled thousands of miles of track and millions in capital each. [p. 19]If the trusts represented horizontal integration, seeking to control a commodity or an industry, the second arrangement was for various "captains of industry" to seize control of a market through the use of vertical integration. The most notorious and successful at this were steel tycoon Andrew Carnegie and oil magnate John D. Rockefeller.

Carnegie sought to justify his power in an essay he wrote for the North American Review which he titled simply "Wealth." The essay is perhaps most famous for the following passage:

It is here; we cannot evade it; no substitutes for it have been found; and while the law may be sometimes hard for the individual, it is best for the race, because it insures the survival of the fittest in every department. We accept and welcome therefore, as conditions to which we must accommodate ourselves, great inequality of environment, the concentration of business, industrial and commercial, in the hands of a few, and the law of competition between these, as being not only beneficial, but essential for the future progress of the race.Rockefeller, as true to his character, was a bit more blunter in asserting a similar philosophy:

The American Beauty Rose can be produced in all its splendor only by sacrificing the early buds that grow up around itThe third form of integration was mainly the brainchild of financier J.P. Morgan, who created the precursor of the modern integrated, multinational corporation by combining his base in banking with what today we term mergers and acquisitions. It was Morgan who arranged for the creation of General Electric and U.S. Steel and created the White Star Shipping Line, parent of the Titanic, on which Morgan was scheduled to travel only to cancel at the last minute.

Parallels with the Present

This history of increasing economic concentration is one reason the 1890s Depression makes it relevant for understanding the current situation. With the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act in 1999, the financial industry underwent both concentration and vertical integration remarkably similar to that of the 1890s.

In 2004, the FDIC notes:

By 2004, three banks exceed a trillion dollars in assets. The number of banks declines. The number of branches increases.This degree of concentration recalls the Gilded Age in which economic concentration reached a degree still unmatched in American history.

Just as no one had ever seen the likes of Standard Oil in the 1890s, no one had ever seen the likes of Citigroup until the repeal of Glass-Steagall. The heads of these financial "trusts" took a page from Rockefeller and Carnegie in justifying their actions, although they refrained from using the Social Darwinian analogies that characterized the Gilded Age.

Instead of roses Sanford Weill of Citigroup evoked sports as his metaphor:

I think life is sort of like a competition, whether it's in sports, or it's achieving in school, or it's achieving good relationships with people. And competition is a little bit of what it's all about.

The 1890s--The Workers

In the 1890s, workers caught in the vise between vertical and horizontal trusts began to organize themselves into unions, experimenting with a variety of organizational strategies and debating whether to follow the example of their European brothers and sisters who had adopted socialism as their philosophy. Throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the dual questions of tactics and philosophy would dominate union politics.

Whatever their organizational preference or philosophical leanings, the workers agreed that their main weapon in the struggle against increasing concentration was the strike. In 1877 a wave of spontaneous strikes broke out in most of the major cities across the country, mostly in the railroads. By the time these strikes were over several hundred were dead and an estimated one thousand wounded. The Great Strikes, as they later were termed, produced such devastation that an informal truce took place between the unions and corporations--until the 1890s Depression.

As for the workers of that time, they lived desperate lives in an era where there were no safety laws, no health Insurance, no unemployment benefits, no arbitration of labor disputes--not even a grievance mechanism should someone be arbitrarily laid off. Workers were totally at the mercy of their employers, some of whom would drive them unmercifully in an effort to make an extra dollar. In many areas wages were based on production--for example, how many tons of coal a worker could mine or load.

It was readily accepted that children would work as soon as they were able, often in Dickensian conditions. In his essay, "In the Depths of a Coal Mine," Stephen Crane described the "breaker boys" who sorted the coal to remove slate and other undesirable material:

Through their ragged shirts we could get occasional glimpses of shoulders black as stoves. They looked precisely like imps as they scrambled to get a view of us. Work ceased while they tried to ascertain if we were willing to give away any tobacco. The man who perhaps believes that he controls them came and harangued the crowd. He talked to the air.

The Bottom Falls Out

On May 5, 1893, a panic not unlike that of the infamous Black Monday of 1929 engulfed the Stock Exchange. National Cordage dropped from its high of 75 two months before to a low of 15. That day GE dropped from 80 to 58 1/2 and ended at 70.

Reflecting on the financial situation the New York Times began with a memorable sentence:

The year 1893 began in doubt and ended in disaster...Its opening found the financial community in a state of serious concern about the currency issue...Banks began to be rapidly drawn upon; contraction of loans followed; and then came the panic...The whole country seemed to be calling on New York for money...How far the decline will go, or how long it will continue, it is no use to try to guess. [December 31, 1893]The article ticked off the firms that had already gone down: National Cordage, the Reading Railroad, the Union Pacific and Great Northern.

Reactions to the 1893 Panic

The reactions to the panic and the resulting 1890s Depression can be best summarized by a roll call of names, some familiar, some obscure: Jacob Coxey, J.P. Morgan, Grover Cleveland, William Jennings Bryan, Eugene Debs and Pullman.

Pullman was the worst. In 1894, workers at the Pullman company went on strike in response to the cuts in wages and layoffs that were rippling through the economy. Strike leader Eugene Debs stated:

The contest is now between the railway corporations united solidly on the one hand and the labor forces on the other.Debs was successful in convincing workers on other railroads to join in sympathy strikes, leading many to wonder if the strikers might bring the nation's railroads to halt. Lead by James J. Hill, the railroad barons put pressure on President Cleveland to end the strike, which he did by calling in 12,000 federal troops under the man who captured Geronimo, Nelson A. Miles. Cleveland's excuse was that the strike impeded the movement of federal mail. In battles between Miles' troops and the estimated 5,000 strikers, thirteen strikers were shot and another fifty wounded. The strikers destroyed some $300,000 in Pullman property.

At about the same time the strike took place, one of those leaders who combine visionary ideals and personal eccentricity that periodically arise in America--especially during times of strife-- began organizing a response to the Depression in his home town of Masillon, Ohio. Jacob Coxey hatched the idea of a march on Washington to demand the government take action to stem the crisis. Coxey was so convinced of the righteousness of his cause that just before the march began he named a newborn daughter Legal Tender.

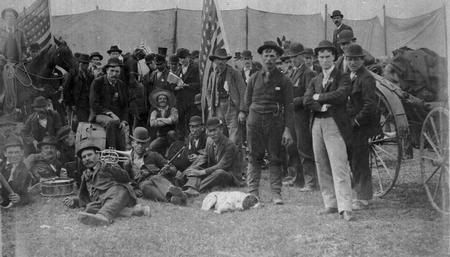

"Coxey's Army," as it became known, was first treated as a joke and then feared as a mob that might bring down the government. Aided by sympathetic citizens in the towns it passed through, the "army" swelled and then shrank to a little over a thousand as it faced a struggle to survive. At one point when toll roads blocked their way, Coxey charted flatboats, paying for his men as freight.

When the army reached the Capitol, Cleveland was determined that Coxey not be allowed to address Congress. As he embarked from a coach on the Capitol steps, Coxey was arrested for "walking on the grass." The "army" dispersed as men glumly walked home in the summer heat. That would have been an ignominious end except that sympathetic representatives began introducing "Coxey Bills" in Congress. One proposed using federal public works to put the unemployed to work. A second allowed state and local governments the authority to issue bonds for local versions for something like the New Deal's Works Progress Administration.

The next two names, J.P. Morgan and William Jennings Bryan both became involved in the issue of whether the federal government should maintain the gold standard. President Cleveland supported the standard while Bryan and others called for using silver as a way of alleviating the financial contraction. At one point pressure on the Treasury became so great that it was forced to borrow money from Morgan to keep from going bankrupt.

By turning to J. P. Morgan in 1894, Grover Cleveland placed the entire nation in debt to the one person many in the country at the time feared would take control of the economy. The action essentially propped up the old system while delaying the birth of a new industrial system based on the idea of a level playing field between workers and management.

Lessons from the 1890s Depression

Grover Cleveland held three sacred beliefs that helped to prolong the 1890s Depression and sent him into the arms of J. P. Morgan: first, he stuck rigidly to the gold standard; second, he did not believe government should intervene on behalf of the unemployed; and third, he saw no problems with the trusts.

It would take three decades to prove Cleveland wrong. The New Deal demonstrated unequivocally the value of the Coxey Bills. As for the gold standard, none other than Ben Bernanke has written and lectured about the wisdom of repealing it at the beginning of the New Deal. In 2004 he told the Federal Reserve Board:

The existence of the gold standard helps to explain why the world economic decline was both deep and broadly international...Perhaps the most fascinating discovery arising from researchers' broader international focus is that the extent to which a country adhered to the gold standard and the severity of its depression were closely linked. In particular, the longer that a country remained committed to gold, the deeper its depression and the later its recovery (Choudhri and Kochin, 1980; Eichengreen and Sachs, 1985)...The finding that leaving the gold standard was the key to recovery from the Great Depression was certainly confirmed by the U.S. experience. One of the first actions of President Roosevelt was to eliminate the constraint on U.S. monetary policy created by the gold standard.Finally, the Glass-Steagall Act did what no one thought possible--it broke up the house of Morgan, forcing the financial giant to split into three entities, the Morgan bank, the Morgan Stanley investment company, and the London security firm of Morgan Grenfell.

The U.S. Bails Out Morgan

Bernanke's considerable academic reputation stems from his research on the Great Depression and his advocating what he has termed the "financial accelerator" theory. According to the Wall Street Journal:

As an academic in the early 1980s, Mr. Bernanke pioneered the idea that the financial markets, rather than a neutral player in business cycles, could significantly amplify booms and busts. Widespread failures by banks could aggravate a downturn, as could a decline in creditworthiness by consumers or businesses, rendering them unable to borrow. Mr. Bernanke employed this “financial accelerator” theory to explain the extraordinary depth and duration of the Great Depression.

In essence Bernanke's theory lies behind the current tactics employed by Dictator of the Treasury Henry Paulson to cope with the current financial crisis, the most recent of which is his decision to invest $250 billion in several prominent financial giants including Citigroup Inc., Wells Fargo & Co., JPMorgan Chase & Co., Bank of America Corp. and Morgan Stanley.

So a century after J. P. Morgan lent money to the Treasury, the Treasury is proposing to lend money to the offspring of Morgan's financial empire.

The Problem with Paulson's Solution

Paulson's solution reminds me of a famous story told often by Abraham Lincoln. As Lincoln spun the tale in his inimitable way, he once came upon a man and a bear engaged in a furious brawl. He asked the man, "How goes it?" According to Lincoln the man answered, "I don't know if I got the bear or the bear's got me."

In the case of Paulson's solution I believe the bear's got us and that bear is the financial industry. J. P. Morgan's propping up of the United States Treasury may have solved a temporary crisis, but in the 1890s borrowing money from Morgan had the impact of stifling more fundamental reforms that were called for and needed at the time.

In much the way Grover Cleveland's action rewarded the J.P. Morgans of the time, Paulson's decision to prop up the big banks is precisely the wrong approach because it rewards, perpetrates and reinforces the very financial "trusts" that share responsibility for the current crisis.

The 1890s represented a degree of economic concentration and integration that is remarkably similar to the financial sector today. What the 1890s Depression signaled and ultimately gave birth to was the belief that firms could be too big and control too much of the market. They were too integrated for the good of the economy and American democracy.

It would take the New Deal and Glass-Steagall to finally break up the "house of Morgan," but the repeal of Glass-Steagall has allowed the formation of its equivalent. For seventy years Glass-Steagall's regulation of the American financial industry essentially kept this country from experiencing a replay of the 1930s or the 1890s. Less than a decade after the repeal of Glass-Steagall we find ourselves facing the most serious financial crisis since the 1930s. Because of the repeal of Glass-Steagall we are not back to the 1930s, but the 1890s.

If we put money into firms that are already too big and too powerful in order to keep them big and powerful then the price should be to breakup and diversify those firms that have been termed "too big to fail." Injecting government funds into the market without making corrections to the market itself is like pouring sand into a sieve.

Conclusion

In short, any money injected into these companies should require a return to something like Glass-Steagall. The money provided to consumers for home, auto and educational loans should not be used to finance the equivalent of high stakes roulette. Nor should businesses that need capital for expansion become financial casinos. That no one seems to want to impose such restrictions is part of the problem. People like Treasury Secretary Paulson are part of the financial culture that created this mess and see nothing fundamentally wrong with the system. People such as Nancy Pelosi made millions from it.

The scary thing about the current crisis is that no one wants to discuss or even propose reform of the system. If the repeal of Glass-Steagall put us back in the 1890s, let us pray we do not have to endure what the people of the 1890s experienced. Henry Adams' quotation may sound as if it could have been written yesterday, but as the Depression of the 1890s should teach us, yesterday is not a good place to be.

Labels: Ralph Brauer