~T. Roethke

Residents of even the tiniest, most insignificant places can love the relics of their past. And when they speak out to defend them, people of good will should take notice.

Readers who know about Turkish affairs will assume that I'm referring to the town of Hasankeyf [discussed here, here, here, and here.], the latest in a series of historical treasures that Turkey's Dam Builders seem determined to inundate. But in fact I'm talking about Cukurca (chew-koor-ja), a town in southeast Turkey situated on the Greater Zab River, with the Iraqi border immediately to the south. Its name in Turkish means a "hollow" in the mountains, a good label for its position among the close-packed border ranges. Before being Turkified, Cukurca's name was Chal (rhyming with doll), and until the 20th century, when the Turks began extending their power into central Kurdistan, it was ruled by a Kurdish Agha. Like so many rulers in this region, however, the Agha of Chal held sway over more than just one ethnic group. While Kurds have always held a large majority within the geographical abstraction known as Kurdistan, there were, until the 20th century, substantial numbers of Jews and Christians to add to the mix. Of this Chal was an excellent example.

In The Cradle of Mankind (1914, 1922), the Anglican missionary W.A. Wigram noted that the Agha of Chal, "an old man", was the Ottoman Mudir (supervisor) of his district, which was part of a larger trans-riverine region known as Berwar. But the Ottoman government no more ruled these mountains than did the Agha: both were shepherds over a flock of cats. Wigram writes:

[The Agha] is also a Sufi by religious profession; and both of these circumstances should make for respectability; for the Mudir is put there to keep order, being lowest on the scale of local governors, and Sufis are usually supposed to be quiet mystics. Many of them are so in fact, and most interesting religious philosophers to talk with; but this man is noted for being on the whole the most crafty murderer in the country-side. It is of course something to rise to eminence in a profession so crowded as that peculiar one is locally; but perhaps that is not the most remarkable thing about this particular Agha. He is the only man of the writer's acquaintance who keeps a really large herd of domestic Jews. Chal village is largely populated by men of that race; and they are to all intents and purposes the serfs of the Agha--his tame money-spinners. The writer was even offered full rights in one of them for the sum of five pounds.Such was the position of these mountain Jews. They were rayah, or "subjects", in local parlance, rather than ashiret (independent tribesmen). Though cribbed and confined, at least they enjoyed a settled feudal position under a lord who (in theory at least) would go after anyone who troubled them. "There are other chiefs who keep 'tame Jews' in this fashion," Wigram wrote, "though not on the same scale as does the wise man of Chal." Wigram, in observing this, reminds the reader that at one time all the Jews of England were the personal property of the King. Indeed, before the Exodus to Israel (after 1948), Jews could be found in all the towns of Kurdistan. There they plied the same trades associated with them in the Christian West: bankers, accountants, money-lenders, shopkeepers, workers in metal, jewelery, and other crafts. When they lived in villages, Jews lived essentially the same life--subsistence farming, stock breeding--as Christian and Kurdish rayahs. In 1850, near the mountain town of Bashkale, south of Lake Van, the archaeologist and explorer Austen Henry Layard came upon a tribe of Kurdish nomads whose clothing and adornments seemed slightly different from others he had met. Then he realized his mistake: these were not Kurds at all but Jews, living in the same black tents that their ancestors had carried with them in the Sinai. This was, as far as I know, the last documented encounter with Jewish nomadism in modern history.

Kurdish Jews spoke Syriac, or neo-Aramaic, a modern version of the same language spoken in Palestine and across the Near East in the time of Jesus. This same Syriac was also--and still is--the language of Kurdistan's Christian population, those "Nestorian" or "Assyrian" Christians which first the American Asahel Grant (1835) and later the English cleric W.A. Wigram went to contact. The Nestorians (Nasturi) were ashiret, the only independent Christian tribesmen in Kurdistan, and they dominated the ranges and narrow gorges to the north of Chal. These people were Christian; but in this context, do not think of St. Francis of Assisi: think rather of Vito Corleone.

The societal patterns of the Kurds were mirrored by those of the mountain Nestorians. An English-speaking reader coming from a middle-class and (at least culturally) Christian background, one habitually biased toward the underdog, might tend to assume that the Nestorians were somehow "nicer" than the Kurds. This--at least at first--was the assumption of the missionaries. It is, however, a dubious proposition. "Blood for blood" was the code by which the mountain Nestorians lived, a code no different from that of [the Kurds]. Frederick Coan, D.D., an American missionary in [Kurdistan] during the last decades of the nineteenth century, loses no love on behalf of the Kurds, and yet in his memoirs (Yesterdays in Persia and Kurdistan, 1939) he gives ample evidence of both sides' willingness to engage in robbery, murder, and subterfuge. His missionary father, Rev. George Coan, wrote in 1851: "The Nestorians are continually embroiled in quarrels. My very soul was made sick by their endless strifes." Close examination of other travelers' stories reveals that they were often just as wary of the Christians as they were of the Kurds. [In fact,] the Muslims of surrounding areas were petrified by the thought of entering their domains. Asheetha, the district where Asahel Grant built his home, was notorious for its plunderers and thieves. W.A. Wigram relates that one tradition among the mountain Nestorians involved raiding Jewish villages every year on Good Friday, in retribution for the death of Our Lord. This he relates as evidence of the mountaineers' boyish energy and high spirits. The reaction of the Jews he does not record. [F&T]Today the Christians are gone, along with the names of their tribes and villages. Only on the Iraqi side of the border do Assyrian villages remain, and many of these have been abandoned due to shelling by the Turkish Army. The same applies to Kurdish villages as well. Faced by random bombardment, for local people the practice of animal husbandry has become next to impossible. In places where Turkish planes have bombed, villagers report hundreds of goats dead, not from the blasts themselves but from something that appears to have poisoned the grass. Goats' milk, a major part of the mountaineers' diet, now makes them ill. Recently a delegation from the Red Cross came to the mountains to take samples from the dead animals. So far no verdict has been issued. Said one Kurd villager in Iraq, "The Turks have done far more to us than Saddam ever did."

On the Turkish side of the border, things are no better. Villages have been forcibly evacuated by the army to deny help to the PKK guerrillas, a policy that has driven Kurds to the larger cities and towns, where they have little chance of employment and lots of time to demonstrate against a government they detest. In Cukurca, a sub-province (ilce) of Hakkari, the population declined drastically during the 1990s, and it remains low today. Indeed, there is little reason to stay. What was once a sleepy backwater has become an artillery base, where Turkish guns fire across the border at "suspected PKK positions" and make life unpleasant for the inhabitants.

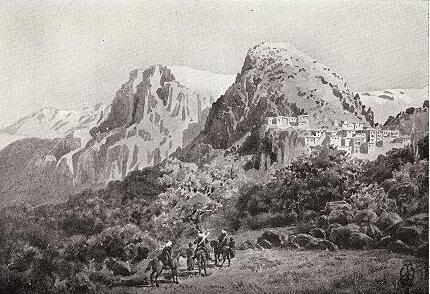

This has taken a toll not only on the residents of Cukurca, but on the main thing that makes their town unique: the ancient buildings and stone houses on the citadel rock in the heart of the village. Look again at the photograph which leads this post. Now look at this drawing:

This was done by Edgar T.A. Wigram, brother of W.A., probably around the year 1910, when the two men were part of the Archbishop of Canterbury's Mission to the Assyrians of Kurdistan. It clearly shows the same citadel rock and the same houses as those in the modern color photo.

And remarkable houses they are. They range between two and four stories in height, and the quality of their stone work far surpasses that of houses usually put up in the mountains. The stone houses of Chal have endured for centuries--some sources say for 1500 years. Not so the peasant houses of Kurdistan, which usually consist of a rectangular excavation in the earth (for earth-sheltered weatherproofing), walls of rough stone stuck together with mud, and a flat roof of poplar logs and branches, plastered over with mud. In earthquakes these dwellings are death-traps. The stone houses of Cukurca, however, live on, their corners sharp and well-laid, their joints secured with lime mortar. Nearby is a large cistern, built to supply the citadel. It's not known who built them (the Emir Saban Medrese, a Muslim madrasa in the town, dates from Ottoman times), but if Chal village was "largely populated" by Jews it's a reasonable assumption that they not only lived in the stone houses but had a hand in their construction.

What time and earthquakes could not do, however, the Turkish Army is completing with its artillery. Their explosive shells may land miles away, but the shock waves from the guns begin in Cukurca. I have never heard a large cannon. Sources tell us that during the Great War their noise carried far from the Western Front and could easily be heard across the Channel in southern England. The thought of multiple batteries surrounding my neighborhood, hammering at the sky throughout the day, fills me with horror. So it has been in Cukurca. Now cracked and increasingly fragile, the houses have been forcibly evacuated by government authorities. But to the anger of residents, nothing is being done to preserve them.

"These houses shine a light into history," says Ziro Koc (pron. coach), a longtime resident. "Their destruction is something that cannot be accepted." Ziro Bey is afraid that one more military operation will cause major damage, and he like others in the town urges the government to embark on an emergency effort to preserve them. These structures, after all, cling to the sides of a very steep slope. Meanwhile, there is little or no employment in the town. Its reason for existence, the surrounding villages and their produce, have evaporated. "Cukurca," says another resident, Faruk Aksac, "is the possessor of many historical and beautiful things. But all this beauty has fallen under the shadow of war." Like so much else, the stone houses of Cukurca appear to be going downhill fast.

[Cross-posted at The Pasha and the Gypsy]

Labels: Cukurca, Gordon Taylor, Hakkari, Kurdistan, tas evler, Turkey, W.A. Wigram

Gordon Taylor on 5/27/2008 3:13 AM:

"Let the Kurds and Turks rot and ruin in their mountains."

Yes, I sometimes feel that way too. I feel that way about the human race, actually. But life is as it is, and was as it was: that is the essence of historical writing. Sometimes you gotta have a strong stomach if you're going to take an honest look at the past. If you're going to condemn every historical edifice to rack and ruin because its builders were serfs, or because they weren't paid enough, or because the people who erected them were tainted by their religiosity or general ass-holishness, then there isn't going to be much left on earth for us to live in or feel affection for. When I lived (1970) at Yas'ur, a kibbutz so far left that at one time in the '50s they had a picture of Stalin in their dining hall, I can't remember anybody enunciating such an absurdity. These were down to earth people, some with numbers on their arms. They sure as hell wouldn't be "stunned" by something as petty as this. As my (Jewish) nephew would say, "Get a grip, dude."

The first Marxist history professor I ever had was Japanese (for interesting historical reasons, the vast majority of Japanese historians are marxists, except for the ones who are die-hard nationalists) who pointed out that the great monuments of Japan -- tombs, Buddhas -- came at the cost of lives: dozens, even hundreds of workers forced to construct paeans to power at great risk.

It was a moment of shock which left me with a lifetime of reservations about the great works of civilization. Sometimes the most fitting thing is to let them crumble, because they honor and benefit the wrong people.

"herd of domestic Jews ... boyish energy and high spirits"

I'm stunned, and angry. Let the Kurds and Turks rot and ruin in their mountains.