by Ralph Brauer | 5/08/2008 10:26:00 PM

Since I wrote my essay on Bill Clinton's repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act and its role in the mortgage crisis, the Internet is full of similar articles. Yet despite this interest in the repeal of Glass-Steagall, the mainstream media refuses to dig deeper into the issue or to press Bill and Hillary Clinton on it.

As is often the case, the story of the repeal of Glass-Steagall and the growth of the subprime mortgage market that is now crumbling around us like a financial house of cards can be best be told by a graph:

Yet critics continue to maintain that Bill Clinton had nothing to do with the present mess. Most of them point out that it was a Republican-dominated Congress that passed the bill that repealed the key parts of what is officially known as the Banking Act of 1933-the 1999 Gramm-Leach-Bliley Financial Services Act (GLBFSA). As pointed out in my earlier essay, Bill Clinton not only signed the bill rather than veto it but also intervened at a crucial stage to assure it passed. One pen he used to sign the bill has a prominent place in the office of former Citigroup CEO and Billionaire Sanford Weill.

A few commenters have pointed that the rise of the graph begins just before GLBFSA, not realizing that one motivation of the bill was that in 1996, former J.P. Morgan director and then Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan had issued a ruling that according to economist Alan Blinder:

Raised [the amount banks could participate in securities] to a degree that, except in some extraordinary cases, it was probably enough for almost any bank to do almost any amount of security underwriting that they'd actually want to do.In 1998, the Clinton Administration essentially looked the other way when Weill created Citigroup from Travelers Insurance, Salomon Brothers, and Citicorp (which owned Citibank). Citigroup plunged into the subprime market so that according to one study:

Nearly three of every four mortgages originated within Citigroup’s lending empire were made by one of its higher-interest subprime affiliates—nearly 180,000 loans out of a total of 240,000-plus mortgages for the year.

A 2003 article by Michael Hudson in Southern Exposure of captures it all:

Citigroup looks the way it does today because Weill bought a middling-sized subprime finance company and used it as a vehicle to acquire other companies and create a behemoth that put him in position to win the biggest prize of all: Citi. The 1998 merger was, at the time, the largest in history, uniting Citicorp, Travelers Insurance, Primerica, Commercial Credit, and Salomon Smith Barney.

Hudson's article details the rise of Sandy Weill which began with his 1986 purchase of subprime lender Commercial Credit. In short, Citigroup--which essentially engineered the repeal of Glass-Steagall--had its beginnings in a subprime lender. But more on that later.

The important point is that since the mainstream media and those with more economic expertise than I possess refuse to connect the dots and fill in the picture, the situation demands a follow-up that specifically details the role of the repeal of Glass-Steagall in the current financial crisis.

The two key questions that need to be asked are: 1) If Bill Clinton had not repealed Glass-Steagall would the current crisis not have occurred or been less severe? and, 2) Do we need to bring back Glass-Steagall? To understand the answers to both questions you need to know exactly what Glass-Steagall prohibited and how the bill that repealed it changed those prohibitions. In short, You need to know a bit of history.

The Mortgage Crisis of the Great Depression

The auctioneer stands in the bed of the horse-drawn wagon surveying the crowd with wary eyes. Two rail-thin deputies with bushy mustaches stand on either side of him casually cradling rifles like hunters walking a field. The auctioneer pounds on the wooden sides of the wagon with a ball-peen hammer to get the attention of the small crowd, each measured stroke echoing like a shot in the enclosed wagon bed.

Off to the side as if trying to hide under the shade of a large elm, stands a man whose face appears almost transparent for its lack of flesh. The sun catches the flash of a tear slowly trickling between his unshaven stubble as he glances down at the ground, avoiding the eyes of the family gathered around him. His wife squeezes his hand as if maybe a drop of hope will come from it while at the same time she gently grips the small fingers of a little girl with what reassurance she can muster.

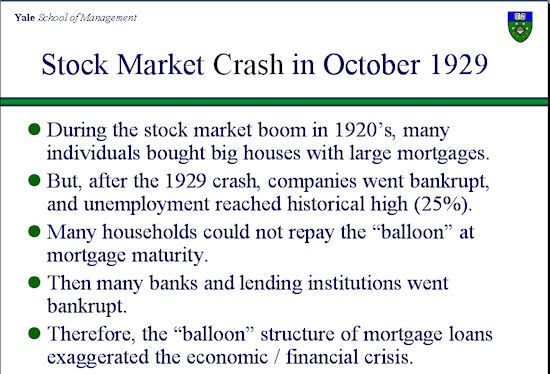

As Hollywood has long recognized, the auctions of the Great Depression remain among its most iconic moments. Yet for all their symbolism, few remember that the financial crisis of the Great Depression also in part stemmed from a mortgage crisis. In the late 1920s, just as today, many banks were making questionable mortgage loans. An excellent PowerPoint presentation by Yale finance professor Zhiwn Chen explains how. I reproduce one slide that represents the key to understanding how mortgages played a role in the Great depression.

Chen points out that in the 1920s, it was routine for mortgages to have only five year terms with a balloon payment at the end.Essentially as the Great Depression worsened, land lost value, so if someone could not pay the mortgage on their farm the bank would seize everything. Hence the auctions.

The Census Bureau's "Historical Census of Housing Trends" shows the impact of those auctions. In 1930 47.8% of Americans owned their own homes, but by 1940 this had fallen to an all-time low of 43.6%. Foreclosures and bank failures created a deadly whirlpool which sucked in many Americans and pulled them under. In addition banks engaged in what John Kenneth Galbraith has referred to as "thimble-rigging:"

This took a variety of forms, of which by far the most common was the organization of corporations to hold stock in yet other corporations, which in turn held stock in yet other corporations.

During 1929 one investment house, Goldman, Sachs & Company, organized and sold nearly a billion dollars’ worth of securities in three interconnected investment trusts—Goldman Sachs Trading Corporation; Shenandoah Corporation; and Blue Ridge Corporation. All eventually depreciated virtually to nothing.

The Background of the Glass-Steagall Act

In the midst of these bank failures, Franklin Roosevelt and his advisors knew something had to be done to protect depositors and bring rationality to the chaos of the financial markets. The man whose name would become attached to what is formally known as the Banking Act of 1933 was a banty rooster from Lynchburg, Virginia who was best known as the father of the Federal Reserve System, which he helped to shepherd through Congress.

Born three years before the start of the Civil War, Carter Glass held on to many old-school, small town values among which had always been a mistrust of stocks and financial manipulation. He first entered the national political stage as a member of the resolutions committee at the famous 1896 convention where he supported the free silver policies of William Jennings Bryan. He may have been the only New Dealer who had actually heard the "Cross of Gold" speech.

In some ways, Glass may have been the last Bryanite--although he and Bryan had their personal differences--for all his life Carter Glass echoed Bryan's opposition to bank speculation. One major disagreement between Bryan and Glass came over the Federal Reserve System, with Bryan and Wilson's then Treasury Secretary William McAdoo supporting governmental control of the system while Glass advocated for private control. In the end President Wilson and Congress created a system that leaned more towards the Bryan/McAdoo point of view.

When he left office as Wilson's Treasury Secretary Carter Glass issued a stern warning about allowing this to happen, but the Coolidge and Hoover Administrations had different ideas. In November 1932 in the waning days of the Presidential election, Carter Glass became so incensed with the statements and policies of Herbert Hoover and his recently-resigned Treasury Secretary, the tycoon Andrew Mellon, that he let loose on both of them in a national radio address that received front page coverage. His descriptions of Galbraith's "thimble-rigging" sound eerily familiar:

With Mr. Andrew Mellon as chairman of the board and the dominant figure, in a single six-month period in 1929 ten of the largest banks in New York alone were given access to $750,000 of Federal reserve credits under the fifteen-day provision of the act. Plainly interpreted, this means that a large, if not greater part of this sum was being loaned to brokers for stock gambling purposes.

Mr. Hoover and Secretary Mellon followed Mr. Coolidge into the stockpit, until these brokers’ loans reached the stupendous total of $8,000,000,000!

Taxes have been abolished that should have been retained. Four million taxpayers, at one swipe, had been released from all obligation to their government. (New York Times, November 3, 1932)

What angered Glass was the policy of Mellon and Hoover to bail out banks that had been playing the stock market using money from the very Federal Reserve system Glass had created! Mellon, by the way, is one of the "forgotten men" Amity Schlaes evokes in her revisionist account of the New Deal.

The Passage of Glass-Steagall

With all the contemporary backpedaling to deny the importance of Glass-Steagall, what many have forgotten is the impact the legislation had on the Great Depression. Had Glass-Stegall not passed, one shudders to think of the alternatives.

In 1931 over a hundred people gathered at the Von Bonn farm in Madison County, Nebraska for a foreclosure auction. A picture of the event (see above) from the Wessels Living History farm in York, Nebraska symbolically captures a knot of people dominating the center of the photograph with a white frame farm house on the left and outbuildings on the right. Whether the photographer intended it or not in the upper right corner a cross-like wooden structure looms over the scene, standing above the flat, treeless prairie horizon and everything else in the frame.

The photograph documents the first of the so-called penny auctions which began spreading throughout the Midwest. Friends and relatives of the foreclosed family would show up, some armed with whatever weapons they could find, to make sure that whatever the auctioneer tried to sell in the name of the bank yielded only a fraction of its value. At the Von Bonn farm the total bids amounted to only $5.35 for an auction in which the bank needed and expected to make hundreds or even thousands of dollars.

Meanwhile in Iowa the radical Farm Holiday movement blocked roads with fence posts, railroad ties and other timbers to prevent crops from reaching the market in an effort to drive up prices. In Sioux City the roads flowed white with milk as farmers poured away their hours of sitting on a milk stool. This liquid blizzard was measured not in inches of snow but in the dollars of debt that poured from each container of milk. It left dark roads enveloped in a slick, white shroud that as the day wore on smelled of the stench of decay.

Glass-Steagall--What Did it Do?

Americans at the time felt as though they had a one-way ticket on a runaway train and none of them would have been surprised to see a skeletal hand on the engine throttle and the Devil himself stoking the firebox. The Glass-Stegall Act pulled the brake chord with such effectiveness that the train virtually slammed to a stop.

Glass-Steagall served as one of the linchpins of New Deal legislation. Had it not passed or passed in weakened form, the American experiment could well have ended. In a systemic sense, the CCC, the WPA and all the other acronyms of Franklin Roosevelt's Brain Trust would have failed without Glass-Steagall to provide financial security. The Act was instrumental in helping to level a playing field that many Americans saw as tilted against them. There is little denying that it kept that milk running in the highway from turning red.

Carter Glass, that old foe of banks entering into the stock market insured that the Banking Act of 1933 contained four key provisions:

- Section 16 - restricted commercial national banks from engaging in most investment banking;

- Section 20 - prohibited any member bank from affiliating in specific ways with an investment bank;

- Section 21 - restricted investment banks from engaging in any commercial banking; and

- Section 32 - prohibited investment bank directors, officers, employees, or principals from serving in those capacities at a commercial member bank of the Federal Reserve System.

With these four provisions, Glass had the preventative measures he felt would avert another financial crisis. Added to these was Steagall's contribution: the creation of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

The success of the Banking Act of 1933 can be measured in part by noting that there were 4,000 bank suspensions in 1933. According to Federal Reserve statistics, a year later only nine insured banks and 52 uninsured licensed banks suspended operations.

It would take over half a century until the country would experience a mortgage crisis of the magnitude of those before Glass-Steagall. Part Two will deal with that crisis and the role the repeal of Glass-Steagall played in causing it.

Labels: Ralph Brauer