This podcast interview with Barbara Slavin was originally posted on my blog on October 21, 2007. At the time, Slavin's book about American-Iranian relations was just published. It also took place shortly before the National Intelligence Estimate with respect to Iran's nuclear program was released to the public.

This podcast interview with Barbara Slavin was originally posted on my blog on October 21, 2007. At the time, Slavin's book about American-Iranian relations was just published. It also took place shortly before the National Intelligence Estimate with respect to Iran's nuclear program was released to the public.This week, President Bush equated negotiating with Iran as "appeasement" during a speech in Israel. The speech appeared to be an attack on presidential candidate Barack Obama who has advocated for diplomatic engagement with Iran. Bush's speech resulted in a firestorm of political acrimony between the Obama and McCain campaigns.

There is considerable ignorance among the American public about Iranian society as well as the back story of American-Iranian relations. Hence, I opted to make this my first post at the new Progressive Historians.

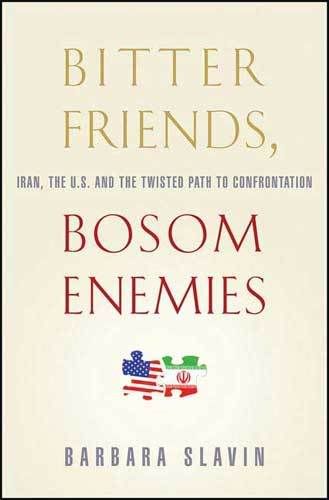

Barbara Slavin, senior diplomatic correspondent for USA Today since 1996 and author of the recently published book, Bitter Friends, Bosom Enemies: Iran, the U.S., and the Twisted Path to Confrontation (St. Martin’s Press), writes that,

“Iran and the United States are like a once happily married couple that has gone through a bitter divorce. Harsh words have been exchanged – husband and wife have come to blows and employed others to inflict more punishment. Apologizing is hard and changing behavior even harder. This relationship is unequal, with one side or the other feeling more vulnerable at any given time and afraid the other will take advantage of concessions.”Currently, the public faces of both nations, presidents George W. Bush and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, have been content to throw rhetorical bombs and raise the diplomatic temperature – increasing the likelihood of war. Indeed, at times it appears that conservative hardliners in both countries are eager for conflict as a means to maintain their respective grips on power.

The journey from the CIA backed coup that overthrew Iran’s democratically elected leader Mossadeq in 1953 and replaced him with the Shah, to the Islamic Revolution of 1979 and current tensions is replete with ill conceived schemes that damaged both nations. Slavin, using her extensive contacts among the powerful inside Iran and the United States, documents missed opportunities for reconciliation between both countries during the administrations of the first President Bush as well as Bill Clinton and George W. Bush.

The combination of her remarkable access to people such as Madeline Albright, Condelezza Rice, Iranian reformers like former President Mohammad Khatami, longtime establishment figures such as Ali Rafsanjani, as well as dissidents like Akbar Ganji and everyday citizens, allows Slavin to shed sunlight on a nation most Americans know very little about. She is also the first newspaper reporter from the United States to interview Iranian President Ahmadinejad.

Slavin has accompanied three secretaries of State on their official travels and reported from Iran, Libya, Israel, Egypt, North Korea, Russia, China, Saudi Arabia and Syria. She is also a regular commentator for U.S. foreign policy on National Public Radio, the Public Broadcasting System's Washington Week In Review and C-Span. This month, she joined the U.S. Institute of Peace as a Jennings Randolph fellow, to continue her research on Iran. Slavin also serves as a member of the Council on Foreign Relations.

Prior to joining USA Today, Slavin was a Washington-based writer for The Economist and the Los Angeles Times, covering domestic and foreign policy issues, including the 1991-93 Middle East peace talks in Washington. From 1985-89, she was The Economist's correspondent in Cairo. During her career, Slavin has traveled widely in the Middle East, covering the Iran-Iraq war, the 1986 U.S. bombing of Libya, the political evolution of the Palestine Liberation Organization and the resurgence of Islamic fundamentalism. Earlier in the 1980s, Slavin also served as The Economist's correspondent in Beijing and reported from Japan and South Korea.

Prior to moving abroad, she worked as a writer and editor for The New York Times Week in Review section and a reporter and editor for United Press International in New York City.

Slavin agreed to a podcast interview with me about her book, Iran and their turbulent relationship with the United States. Please refer to the media player below. Our conversation is just under thirty minutes. This interview can also be accessed at no cost via the Itunes Store by searching for “Intrepid Liberal Journal.”

Labels: Barbara Slavin, George W. Bush, Iran, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Robert Ellman

Robert Ellman on 5/17/2008 11:32 AM:

He was elected to the Iranian parliament, Majilis in 1944. The Majilis with their democratically elected members, made Mossadeq Prime Minister in 1951. So in fairness, Mark definitely has a point that I should have accounted for when I originally posted this. However, he was overthrown by the CIA two years later and I would argue the repercussions of that policy have not been positive.

Among other things, Mossadeq was an avowed nationalist opposed to any imperialism against his country.

Time Magazine named Mossadeq their Man of the Year in 1951. Click here to read it. It's a fascinating article.

As for my interview with Barbara Slavin, it's especially curious to me that much of my email afterwards was about the growing drug problem among Iranian youth that we discussed. Our conversation covered a range of issues about Iran and the American/Iranian relationship yet that was the issue that motivated people to email me about it later.

Howdy Jeremy,

Initially, Mossadegh was exceedingly popular as were his moves against Anglo-Persian oil facilities. It would only be fair to describe the relationship between British oil interests and Iran as vampiric. Iranians hated the British more or less uniformly. The Shah's father, Shah Reza Pahlavi had tried to break the hold of the British on Iran but failed ( and was later deposed during WWII mostly at British insistence)

Mossadegh became less popular in part due to the economic costs of his conflict with Britain and partly because of his own mishandling of other Iranian factions ( tudeh, clergy, army, monarchists). The majlis, which had elected Mossadegh with overwhelming support later turned against him & Mossadegh ruled with emergency powers during his second prime ministership.

Operation Ajax, the CIA coup to which Robert aluded only worked ( in my view) because Mossadegh had politically isolated himself by that time, something his rep as a "martyr" obscures. It is also my view that had Mossadegh given a better impression in his meeting with high level State Department officials ( his trademark histrionics left Eisenhower's representatives completely mystified) Eisenhower might have never permitted it, not being overly sympathetic to the claims of British imperialism ( a contempt he put on dispay during the later Suez crisis).

Was it a good idea to overthrow Mossadegh ? If Mossadegh had fallen, the Tudeh would have had a reasonable opportunity to seize power in Teheran. So might have the Army as later happened in next door Iraq. Hard to say. Mossadegh never properly consolidated power enough to point to a likely "natural" successor. Eisenhower and Dulles were not willing to entertain the risk of Iran becoming a Soviet satellite, which may be why they could live with Nasser ( an unfriendly but non-communist "strong" ruler who crushed his opposition) but toppled Mossadegh, who was "weak".

"The journey from the CIA backed coup that overthrew Iran’s democratically elected leader Mossadeq in 1953 and replaced him with the Shah"

Mossadegh usurped power, both of the Shah's and of the Majlis. "Legally appointed" would be a better descriptor.

Dr. Mossadegh was many things - a reactionary scion of the old Qajar dynasty, a gifted orator, a sincere nationalist, vehemently anti-British, a longtime opponent of the Pahlavis - a democrat he was not, nor even a constitutionalist. He was on a trajectory to strongman, secular-nationalist rule that was common to the period.

Ironically, Mossadegh and the Shah he despised had more in common in terms of ambitions for Iran's development than either did with the Tudeh or the Shiite clergy.