by Ralph Brauer | 5/14/2008 10:08:00 PM

Hillary Clinton's convincing win in West Virginia has convinced me that we need a real convention and not some made-for-TV pseudo-event. That is the only fair way out of the present mess.

Although I have criticized Clinton's tactics and am no lover of the political philosophy of the Democratic Leadership Council, politics should not get in the way of fairness. Clinton has clearly earned the right to attend the convention as a candidate. I would love to see john Edwards there also and any other candidate who has picked up a delegate. Clinton has also earned the right to continue this campaign.

The Forbes Delegate Meter shows that neither she nor Barack Obama can win the nomination without the support of a majority of the superdelegates. All of this, of course, precludes Florida and Michigan. My personal opinion is that Clinton "cheated" to win these two states. She knew Obama would not run a campaign in either state, so she entered the contests knowing she would be the only one running.

Yet the two states deserve to attend the convention. The Democrats need both states to win the White House, but more important, the Party needs to heal and part of healing is to forgive. My solution is to split the delegations 50-50, which would be the most equitable solution. For those who think Clinton would have won both states, it would penalize Clinton for breaking the rules.

With those two states seated, we come to the superdelegates. They should not decide the winner. Because they are not chosen by the people, they should not even be allowed to vote. For the superdelegates to decide the race runs counter to everything this country stands for and that the Democratic Party SHOULD stand for. If the superdelegates decide the winner, supporters of the loser will inevitably cry "foul." They will believe a deal has been cut or some of the delegates were "bought," which if rumors are true may well be the case.

In short we need to have a real convention--an old-fashioned fire-eating, ballots into the wee hours of the morning contest. We need to let THE PEOPLE decide not a bunch of Party bureaucrats and retreads from the past. With the superdelegates relegated to the sidelines, the convention should hold delegates to their designated candidate on the few first few ballots only and then turn them loose.

Both parties seem afraid of real conventions these days. They have turned them into boring, pseudo-events where every detail is scripted like a Hollywood film and everything we see is just as real. The event becomes an over-long infomercial and just as bad as an hour with the Ronco pocket fisherman.

It is hard to believe, but many Americans have never seen, let alone participated in, a real convention so they have no idea what they look like. So let me describe one where the situation was remarkably like todays. In 1912 the Democratic Party was split between progressives and conservatives, much as it is today. Three candidates with any realistic hope of winning entered the stone armory in Baltimore that housed that convention: House Speaker Champ Clark, House Majority Leader Oscar Underwood and New jersey Governor Woodrow Wilson. Clark was the acknowledged front-runner. There was one undeclared candidate everyone both feared and hoped for: William Jennings Bryan, who controlled the progressive wing and had won the nomination three times.

The delegates gathered there expected a protracted fight-and fights they got, as the Baltimore police were kept busy trying to keep order, including one memorable moment when the banners of two marching armies of opposing candidates met in front on the speakers' platform and like troops on a battlefield tried to capture their opponent's colors. At one point the police formed a gauntlet in front of the armory through which delegates and others possessing credentials had to march before entering the floor.

The convention also featured the usual side shows. A prudish reporter for the New York Times noted, "The theatrical intrusion of girls to incite cheering became unbearable." He softened his criticism by observing, "The intruding young woman, particularly if she is good-looking and has an inspiriting personality, may produce very good results in a political convention."

The nominations actually took all night because back then states nominated "favorite sons," usually a governor they wished to give a moment in the limelight and also showcase for a future run at the presidency or a shot at the Vice Presidency or a cabinet post. As a result the first ballot had votes for eight candidates, four of whom had over 100 votes.

Clark took the early lead with Wilson in second, Underwood and Ohio Governor Judson Harmon following. Still no one could get a clear majority. On the tenth ballot Tammany Hall boss Charles Murphy threw his support to Clark, giving him a majority. In every previous convention, at this point the delegates would move to provide the necessary two-thirds to clinch the nomination. But this time that did not happen. One of the old prairie firebrands, Oklahoma's "Alfalfa Bill" Murray shouted, "Is this convention going to surrender to the Tammany Tiger?" The answer from the delegates was, "No!"

Instead of switching to Murphy the Wilson and Underwood delegations held firm. Woodrow Wilson, who had battled Clark since the opening of the convention waited for news at the New Jersey summer governor's mansion in the poetically named town of Sea Girt. As the waves pounded an incessant rhythm in the background of the house designed to replicate George Washington's headquarters at Morristown, floor manager William McCombs called Wilson on Saturday morning to tell him his case was hopeless. McCombs recommended Wilson release his delegates to Underwood. Wilson's private secretary Joseph Tumulty, who was with him at the time, says on hearing this Wilson's wife put her arms around her husband to console him. Wilson began to prepare a concession letter to Clark.

But again events intervened. On the floor Wilson delegate Roger Sullivan rushed over to McCombs and told him, "Damn you, don't do that." After a hasty conference at Sea Girt, Wilson decided to not release his delegates and the convention went on.

Then came one of the most dramatic moments in American convention history. On the fourteenth ballot, a familiar figure stood up and began to speak in a voice that resonated with everyone on that floor, a voice so clear and penetrating his followers likened him to a Biblical prophet. The voice made him the main attraction of his times, enabling thirty years of road tours that would have him deliver over six thousand public addresses and thousands more spontaneous speeches anywhere he had an audience. The voice allowed him a huge advantage over his rivals, for whether in a cavernous convention hall or the tent of a rural Chautauqua, the voice had the power to project almost superhuman distances. Without a microphone, the voice could reach an incredible 30,000 people in the open air-the population of a fair-sized Midwestern town.

It was the voice of William Jennings Bryan, the voice that had delivered the most famous convention speech in American history, the 1896 "Cross of Gold Speech," whose ringing conclusion many of those delegates could recite by heart:

If they dare to come out in the open field and defend the gold standard as a good thing, we shall fight them to the uttermost, having behind us the producing masses of the nation and the world. Having behind us the commercial interests and the laboring interests and all the toiling masses, we shall answer their demands for a gold standard by saying to them, you shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns. You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.

To punctuate this ending, Bryan employed the dramatic gestures of the turn-of-the-century stage, gestures which today would seem overblown, bringing his hand to his head at the mention of the crown of thorns and then spreading his arms wide, holding the pose so no one would miss its meaning. Bryan realized the significance of his speech, writing, "the situation was so unique and the experience unprecedented that I have never expected to witness its counterpart." What he was about to say would come close and in terms of its impact arguably may be more important.

When Bryan rose to speak on the fourteenth ballot, delegates did not know what to expect. He had come to the convention as a Clark delegate, but Clark's acceptance of support from Murphy crossed a line. Earlier in the convention Bryan had tried several maneuvers in order to neutralize the New York delegation Murphy controlled because Bryan felt it represented the interests of Wall Street, interests he had fought against his entire political career. When Clark accepted the support of Murphy it crossed a line for Bryan and everyone in that convention hall knew it.

Some thought he might be announcing his own candidacy. Others suspected Bryan was about to pull one of his celebrated convention maneuvers (Bryan may rank as our most accomplished convention tactician). All expected a taste of the celebrated Bryan oratory.

Bryan did not disappoint, announcing that he was switching his vote to Woodrow Wilson. Clark's supporters tried to drown him out with boos and hisses. Delegates broke into fistfights even as Bryan was finishing what may well have been the second most important convention speech of his life.

Tumulty, Wilson and Clark all would state that without Bryan's support Wilson would not have won the nomination. Clark was so incensed by what he termed a "betrayal" he went to his grave a sworn enemy of Bryan. Wilson would reward Bryan with the post of Secretary of State. Yet it would take many more ballots before Wilson would win the nomination on the 46th ballot.

Whether a 2008 Democratic Convention would be as dramatic as that of almost a century ago, one thing is certain, it would be a plus for the Democratic Party. First it would show that Democrats believed in the will of the people and were willing to let the people decide. For the Party itself, the prospect of an open convention would attract far more viewers than a scripted affair. It would be nothing less than the supreme political drama of this already dramatic election year.

It also would acknowledge several facts that everyone keeps wanting to deny. First, the contest has changed with each primary. Would the Iowans who voted for Obama in January vote for him now? Would the New Hampshire residents who voted for Clinton vote for her now? What has become clear is that each candidate represents a base of voters the Democrats need to win in November.

A scripted convention with a television-like Oprah or Dr. Phil reconciliation between Clinton and Obama will not bring these voters together. They need the chance to work it out at the convention, not let superdelegates decide for them. That is also why it is important that Edwards' delegates also be seated and he be among the candidates. Biden, Dodd, Kucinich and Gravel also deserve to have their names placed in nomination. If someone wants to, you can even add Al Gore to the list, since his name keeps getting mentioned as a possible compromise.

One of them just might be another Woodrow Wilson. In the end the objective is to take the leashes off the Clinton and Obama delegates and let them make their own decisions and if neither of the two can command a majority, perhaps a third candidate can. The time has come to open up the process, not shut the door.

Bryan himself said it best in "Cross of Gold:"

My friends, it is simply a question that we shall decide upon which side shall the Democratic Party fight. Upon the side of the idle holders of idle capital, or upon the side of the struggling masses? That is the question that the party must answer first; and then it must be answered by each individual hereafter.

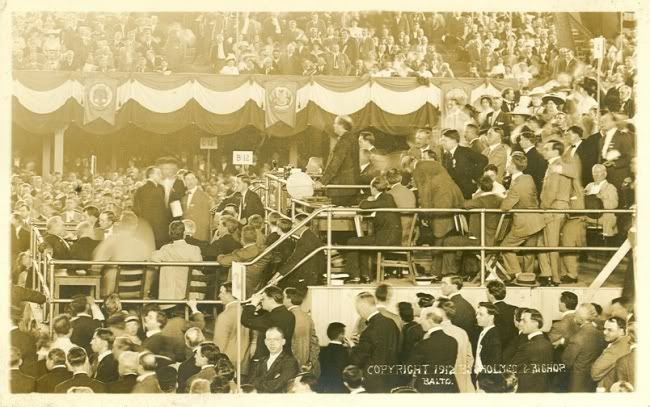

NOTE: The above photograph took a bit of research to find. It is an extremely rare and valuable picture that captures Bryan on the platform as he presented one of the most controversial motions in convention history. The palm leaf fan in the speaker's hand is a dead give away that it is Bryan since the fan was almost as much a part of his image as his Stetson hat.

Bryan had entered the convention hall before the session began so he could command a seat at the very front of the speakers platform. When the session opened he stood up and began speaking, moving what became known as the infamous Morgan-Ryan-Belmont resolution which sought to evict these Wall Street financier/delegates from the convention.

Bryan's maneuver was designed to force a vote that would reveal the true feelings of the Clark delegates. The resolution touched off another riot. It failed, but Bryan had accomplished his purpose, it tipped the hand of Murphy (who at the point was supporting Harmon) and the Clark delegates. It is yet another example of why old-fashioned conventions were not only more fun but served as hothouses for nurturing leaders. The Baltimore convention was a true hothouse in late June in the days before air conditioning .

Labels: Ralph Brauer

Permalink

2 Comments:

They were introduced at some point between 1972 and 1980. I've heard two different stories, one suggesting they were instituted to keep party outsiders like McGovern from winning the nomination, the other substituting Carter for McGovern. I'm inclined to believe the former story, because if they were instituted between 1976 and 1980 that would have required Carter's complicity as a sitting president, and I doubt that would have been forthcoming.

I believe it was because of this convention that superdelegates were first introduced and invented. The likes of Bryan and Clark did not want this sort of thing to happen again. Does any progressive historian know how they became involved in the process and by whom it was started?