by midtowng | 4/05/2008 01:22:00 PM

360 years ago today a fleet of Spanish warships sailed into the harbor in Naples, Italy, and ended the first real experiment in popular democracy in the western world since dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla marched his armies into Rome seventeen centuries earlier.

The proletariat government of Naples collapsed without firing a shot, which is a sad statement that hardly represents the spirit of revolt that captured the city just 9 months earlier.

That short, exciting year in southern Italy was the prelude to two and a half centuries of revolts and revolutions in Europe. It clearly demonstrated both the strengths and weaknesses of both empires and popular democracy.

Background

Early in the 16th Century the Kingdom of Naples had become part of the Spanish-dominated Hapsburg Empire, thus becoming the primary flashpoint for wars between Spain and France for the next two centuries.

All those wars are expensive, and the costs of putting armies into the field year after year drove both the Spanish and French empires to bankruptcy time and time again. This drove the tax rates on the citizens of the Hapsburg Empire to unsustainably high levels.

By the 1640's the population Naples had reached 300,000, which made it the 2nd largest city in Europe (after Paris), and the most densely populated.

Spain exerted little influence and affairs were generally handled by the local nobility, which abused their power for their own enrichment. Jobs were scarce, taxes were high, and justice could be bought, all in an overcrowded city.

In 1646 the Duke of Arcos arrived as Viceroy of Naples. He came with orders from Spain to send one million ducats back a year. He decided to meet that target by taxing the sale of fruit, the ordinary food of the poor.

On Christmas Eve 1646, an angry mod surrounded the Viceroy while on his way to mass, and forced him to agree to rescind the tax on fruit. But once safe from the mob he decided to do nothing. It was to be a bad decision.

In May 1647, a popular procession marched in the cathedral in Palermo and stuck a pole crowned with bread on the high alter. There were shouts of "Down with taxes and bad government!" The mob then set fire to the town hall, demolished the tax offices and opened the prisons. In order to calm the unrest, the Duke of Arcos abolished the tax on fruit for the people of Palermo on May 20.

The people of Naples noticed.

The Revolt of Masaniello

Tomaso Aniello d'Amalfi (aka Masaniello) was an illiterate, Neapolitan fisherman and smuggler, and was very popular in the area.

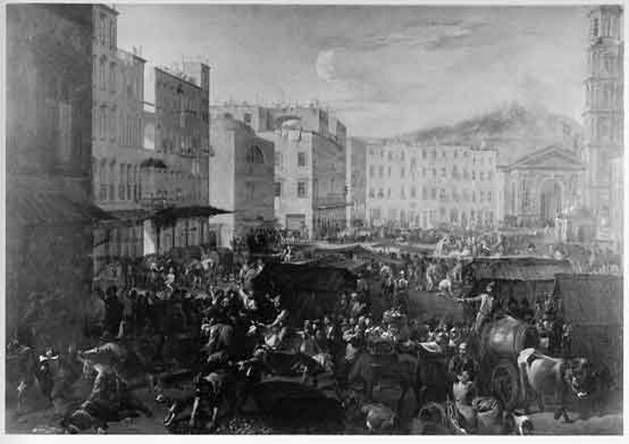

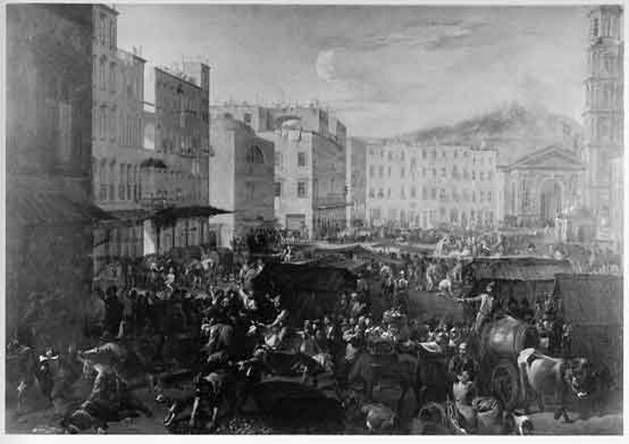

On July 7 of every year was the Feast of the Madonna of the Carmine held in the Piazza Mercato. During which a mock battle between the people and Turkish invaders was acted out. Masaniello was in charge of leading a mock army to fight the Turks.

The piazza was a teaming, filthy place. It was crowded with vendors and soldiers. It contained the city's gallows and displayed various torturing devices.

Most importantly, it was the place you came to pay your taxes.

During the mock battle a rumor reached the crowd that yet another tax on fruit had been signed into law. Masaniello, in true Robin Hood-style, transformed his mock army into a real army.

"Long live the King! Down with bad government!"

- the cry of the Masaniello revolt

Masaniello's ragtag army attacked the tax collector stalls and customs offices first. The army kept moving, gaining followers as it left the crowded piazza. It then made a direct bead on a nearby home of an infamous tax collector by the name of Girolamo Letizia, which was burned.

By now the mob numbered in the tens of thousands. They forced their way into the palace of the hated Count d'Arcos, who was forced to flee to a nearby castle.

Masaniello tried to keep the mob from engaging in vandelic tendencies, and to a large extent he succeeded. He administered justice from outside his house. He was elected elected Captain of the People. A few rioters, such as the duke of Maddaloni, who came to Naples to cause trouble, were sentenced to death and executed.

Troops who were called in from outside the city were driven off by the enormous size of citizen army, now better armed. The revolt began spreading outside the city to the provincial areas.

The Viceroy arranged a meeting with Masaniello where he quickly agreed to most of his demands. These included:

Masaniello was not the brains behind the revolt. An 80-year old priest named Giulio Genoino was.

By the time of this revolt, Genoino had spent about 20 years in prison or exile for spreading sedition in connection with riots in 1585 and 1620. He had been in contact with Masaniello from even before the revolt and was directing his actions from behind the scenes.

The problem was that Masaniello was acting more and more erratically.

Starting just a few days after the revolt, Masaniello's behavior began to drift towards the bizarre.

No one knows for certain, but most historians agree that he had been poisoned. Not to kill him and therefore make him a martyr, but to discredit him.

And so end's the Masaniello's Revolt, after just nine days. But the story doesn't end there.

The First Neopolitan Republic

The death of Masaniello left the revolt without a clear leader, and the movement quickly splintered into factions. By the middle of August the rebels had grown tired of Guglio Genoino, so they elected a gunsmith named Gennaro Annese as their new leader.

Annese had none of Masaniello's charisma, but he was a capable leader. On August 21 the rebels attacked and conquered a Spanish garrison at Santa Lucia. The following day a small Spanish fleet bombarded the crowded city. A truce was declared and the Viceroy caved in to more of the rebels demands.

But it was only a ploy. D'Arcos was playing for time until the real Spanish fleet arrived.

The city had been mostly pacified by the time a spanish fleet under the command of Don Juan José de Austria (aka John of Austria the Younger) arrived in the harbor in October. Instead of simply letting the exhausted rebels return to their lives of poverty, he decided "to soothe the last insurgents" by firing cannons into the crowded city. They took back the center of the city, but the rebels retained control of the perimeter, the high ground on the hills of Posillipo, Vomero and Capodimonte.

The revolt sprung anew, but this time it had a decidedly anti-Spanish flavor. The army was expelled from the city a second time and a republic was declared on October 22.

This time they appealed for foreign assistance - the French.

Henry II, The Duke of Guise accepted the offer to be the "doge" of Naples. On November 15, 1647, he arrived in Naples to a hero's welcome.

The Duke had no real support in the French Court, so either he overestimated his power in this regard, or the people of Naples did. Plus, October of 1647 marked the end of the brutal 30 Years War, which left almost all of Europe bankrupt and exhausted from conflict and death.

France was not going to be willing to go to war with Spain over Naples at this time. Naples was on its own.

"[The Duke of Guise] left his betrothed in France, his wife in Flanders, his whore in Rome and would leave his hide in Naples."

- popular jibe of the time

This only made things more complicated. The new "doge" may have been nominally in charge, but Annese was still military commander there. Plus, the nobility of Naples was still loyal to the Spanish crown, and waited for their opportunity to betray the rebels. The various rebels groups spent their time bickering over whether they should be "a bourgeois democratic, oligarchic, federated, constitutional, or military republic, on Dutch, Swiss, Venetian, or new models."

While all this was going on, the Spanish had replaced viceroy d'Arcos with John of Austria.

Henry II was inept at dealing with the people of Naples and by February there had developed an anti-Guise conspiracy within the city. It was on the 22nd of this month that a military attempt by the rebels was made against nearby Spanish strongholds. It failed and things settled down into a stalemate.

This failure signaled to the local nobility that their time to betray the revolution was near. John of Austria infiltrated the city with spies and began consolidating the loyal opposition. John also offered to repeal the most hated taxes, more representation from the popolo in the government, and amnesty to all the rebels.

On April 5, 1648, the new Viceroy, Inigo Velez de Guevara, Count of Ognate, landed near Naples with a large army and marched into the city virtually unopposed. The only resistance came from the camp of Gennaro Annese. Henry II had already betrayed the people he was supposed to protect, and agreed not to mount any resistance, while also moving his camp outside of the city walls.

The Spanish would rule in Naples for another 48 years.

The proletariat government of Naples collapsed without firing a shot, which is a sad statement that hardly represents the spirit of revolt that captured the city just 9 months earlier.

That short, exciting year in southern Italy was the prelude to two and a half centuries of revolts and revolutions in Europe. It clearly demonstrated both the strengths and weaknesses of both empires and popular democracy.

Background

Early in the 16th Century the Kingdom of Naples had become part of the Spanish-dominated Hapsburg Empire, thus becoming the primary flashpoint for wars between Spain and France for the next two centuries.

All those wars are expensive, and the costs of putting armies into the field year after year drove both the Spanish and French empires to bankruptcy time and time again. This drove the tax rates on the citizens of the Hapsburg Empire to unsustainably high levels.

By the 1640's the population Naples had reached 300,000, which made it the 2nd largest city in Europe (after Paris), and the most densely populated.

The flood of migration from the provinces was encouraged in great part by the viceregal decision to exempt the city, from direct taxes, while at the same time increasing the burden of taxation on the provinces and continuing to maintain in the city what the administration judged to be (unwisely, as it transpired) a less politically sensitive policy of indirect taxation. This urban influx added considerable strain to an already stretched metropolis. The philosopher Tommaso Campanella, for example, estimated that no more than a sixth of the Neapolitan population worked. Although probably exaggerated, his words attest to the growing recognition of a volatile urban underclass, living more or less hand to mouth and referred to disparagingly as either the canaille (canaglia, pack of dogs, rabble) or the lazaruses (lazzari), a term originally reserved for lepers but now extended to the poorest of the poor.The city was hard to manage even by good government, but Naples had no good government.

Spain exerted little influence and affairs were generally handled by the local nobility, which abused their power for their own enrichment. Jobs were scarce, taxes were high, and justice could be bought, all in an overcrowded city.

In 1646 the Duke of Arcos arrived as Viceroy of Naples. He came with orders from Spain to send one million ducats back a year. He decided to meet that target by taxing the sale of fruit, the ordinary food of the poor.

On Christmas Eve 1646, an angry mod surrounded the Viceroy while on his way to mass, and forced him to agree to rescind the tax on fruit. But once safe from the mob he decided to do nothing. It was to be a bad decision.

In May 1647, a popular procession marched in the cathedral in Palermo and stuck a pole crowned with bread on the high alter. There were shouts of "Down with taxes and bad government!" The mob then set fire to the town hall, demolished the tax offices and opened the prisons. In order to calm the unrest, the Duke of Arcos abolished the tax on fruit for the people of Palermo on May 20.

The people of Naples noticed.

The Revolt of Masaniello

Tomaso Aniello d'Amalfi (aka Masaniello) was an illiterate, Neapolitan fisherman and smuggler, and was very popular in the area.

On July 7 of every year was the Feast of the Madonna of the Carmine held in the Piazza Mercato. During which a mock battle between the people and Turkish invaders was acted out. Masaniello was in charge of leading a mock army to fight the Turks.

The piazza was a teaming, filthy place. It was crowded with vendors and soldiers. It contained the city's gallows and displayed various torturing devices.

Most importantly, it was the place you came to pay your taxes.

During the mock battle a rumor reached the crowd that yet another tax on fruit had been signed into law. Masaniello, in true Robin Hood-style, transformed his mock army into a real army.

"Long live the King! Down with bad government!"

- the cry of the Masaniello revolt

Masaniello's ragtag army attacked the tax collector stalls and customs offices first. The army kept moving, gaining followers as it left the crowded piazza. It then made a direct bead on a nearby home of an infamous tax collector by the name of Girolamo Letizia, which was burned.

By now the mob numbered in the tens of thousands. They forced their way into the palace of the hated Count d'Arcos, who was forced to flee to a nearby castle.

Masaniello tried to keep the mob from engaging in vandelic tendencies, and to a large extent he succeeded. He administered justice from outside his house. He was elected elected Captain of the People. A few rioters, such as the duke of Maddaloni, who came to Naples to cause trouble, were sentenced to death and executed.

Troops who were called in from outside the city were driven off by the enormous size of citizen army, now better armed. The revolt began spreading outside the city to the provincial areas.

The Viceroy arranged a meeting with Masaniello where he quickly agreed to most of his demands. These included:

political representation equal to that of the nobility for the population, and a reinstatement of the privileges given the city by the Emperor Charles V, exempting the city from all but the most essential taxation.How did an illiterate fisherman come up with such revolutionary demands such as these? He didn't.

Masaniello was not the brains behind the revolt. An 80-year old priest named Giulio Genoino was.

By the time of this revolt, Genoino had spent about 20 years in prison or exile for spreading sedition in connection with riots in 1585 and 1620. He had been in contact with Masaniello from even before the revolt and was directing his actions from behind the scenes.

The problem was that Masaniello was acting more and more erratically.

Starting just a few days after the revolt, Masaniello's behavior began to drift towards the bizarre.

No one knows for certain, but most historians agree that he had been poisoned. Not to kill him and therefore make him a martyr, but to discredit him.

On July 16, after giving a rambling, incoherent declaration to the people, he stormed into a church and disrobed. At that point, obviously helpless and useless, he was dragged into a room in an adjacent monastery and murdered, probably by hired assassins. They severed his head and took it to the viceroy.The following day, in true ancient Athens fashion, the fickle populace had a change of heart. They dug up Masaniello's body, retrieved the head, and gave him a hero's burial in the Church of the Carmine.

And so end's the Masaniello's Revolt, after just nine days. But the story doesn't end there.

The First Neopolitan Republic

The death of Masaniello left the revolt without a clear leader, and the movement quickly splintered into factions. By the middle of August the rebels had grown tired of Guglio Genoino, so they elected a gunsmith named Gennaro Annese as their new leader.

Annese had none of Masaniello's charisma, but he was a capable leader. On August 21 the rebels attacked and conquered a Spanish garrison at Santa Lucia. The following day a small Spanish fleet bombarded the crowded city. A truce was declared and the Viceroy caved in to more of the rebels demands.

But it was only a ploy. D'Arcos was playing for time until the real Spanish fleet arrived.

The city had been mostly pacified by the time a spanish fleet under the command of Don Juan José de Austria (aka John of Austria the Younger) arrived in the harbor in October. Instead of simply letting the exhausted rebels return to their lives of poverty, he decided "to soothe the last insurgents" by firing cannons into the crowded city. They took back the center of the city, but the rebels retained control of the perimeter, the high ground on the hills of Posillipo, Vomero and Capodimonte.

The revolt sprung anew, but this time it had a decidedly anti-Spanish flavor. The army was expelled from the city a second time and a republic was declared on October 22.

This time they appealed for foreign assistance - the French.

Henry II, The Duke of Guise accepted the offer to be the "doge" of Naples. On November 15, 1647, he arrived in Naples to a hero's welcome.

The Duke had no real support in the French Court, so either he overestimated his power in this regard, or the people of Naples did. Plus, October of 1647 marked the end of the brutal 30 Years War, which left almost all of Europe bankrupt and exhausted from conflict and death.

France was not going to be willing to go to war with Spain over Naples at this time. Naples was on its own.

"[The Duke of Guise] left his betrothed in France, his wife in Flanders, his whore in Rome and would leave his hide in Naples."

- popular jibe of the time

This only made things more complicated. The new "doge" may have been nominally in charge, but Annese was still military commander there. Plus, the nobility of Naples was still loyal to the Spanish crown, and waited for their opportunity to betray the rebels. The various rebels groups spent their time bickering over whether they should be "a bourgeois democratic, oligarchic, federated, constitutional, or military republic, on Dutch, Swiss, Venetian, or new models."

While all this was going on, the Spanish had replaced viceroy d'Arcos with John of Austria.

Henry II was inept at dealing with the people of Naples and by February there had developed an anti-Guise conspiracy within the city. It was on the 22nd of this month that a military attempt by the rebels was made against nearby Spanish strongholds. It failed and things settled down into a stalemate.

This failure signaled to the local nobility that their time to betray the revolution was near. John of Austria infiltrated the city with spies and began consolidating the loyal opposition. John also offered to repeal the most hated taxes, more representation from the popolo in the government, and amnesty to all the rebels.

On April 5, 1648, the new Viceroy, Inigo Velez de Guevara, Count of Ognate, landed near Naples with a large army and marched into the city virtually unopposed. The only resistance came from the camp of Gennaro Annese. Henry II had already betrayed the people he was supposed to protect, and agreed not to mount any resistance, while also moving his camp outside of the city walls.

The Spanish would rule in Naples for another 48 years.

Labels: midtowng