by Ralph Brauer | 4/04/2008 01:17:00 PM

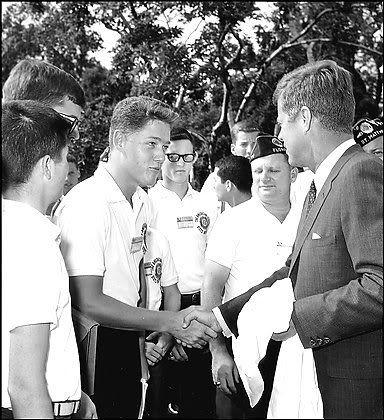

Bill Clinton gripping John Kennedy's hand represents one of the twentieth century's iconic images, for although neither of them knew it at the time, that handshake symbolized the end of the American Century and the values of the Democratic Party that stretched back to William Jennings Bryan.

For someone who has always known the power of his voice it took him longer than one might expect to learn to use it for public speaking. In small groups or with one or two people it has been with him so long he probably cannot remember when he did not have the gift. A half century or so before in the place where he was raised the gift might have preordained him to the ministry, but in an electronic world he dreamed different dreams. His childhood nanny, Miss Walters, told him "he might be a minister like Billy Graham some day." [David Maraniss, First in His Class, p. 35]

In the haphazard flow of childhood conversation he could improvise like a great jazz musician, so as a youngster he had a tendency like all prize pupils to want to show off his talent. That quality prompted David Maraniss to title his Clinton biography, First In His Class. Maraniss reports that one of his grade school teachers gave him a "C" for being a "busybody" because he raised his hand so much. Raising your hand too much plus his lack of athleticism and large, sometimes pudgy body might have made him a ready target for taunts and pranks, but the voice helped him to overcome his liabilities, so much that one schoolmate remembered that he naturally liked people and people liked him.

It is difficult not to be psychoanalytical about the voice, for as the child of an alcoholic and sometimes violent father, Bill Clinton must have had to use that voice to keep himself and his family from shattering into broken shards. His childhood stories stress physical confrontations, which came after Clinton had grown, but as a little boy the voice was his only weapon keeping he and his mother from perhaps ending up in the emergency room or worse.

The voice and his ambition must have fed on each other, motivated by his desire to transcend his reality. For Bill Clinton getting out became more than a boy's fantasy to sustain him in rough times. Small town people, particularly those who do not fit in, have longed dreamed of moving away. During the Depression Hollywood beckoned. Recently thirty seconds of fame on television entices those who should know better. But Bill Clinton had the biggest dream of all, one that could have earned him more ridicule than a tone-deaf American Idol contestant if he had not had the voice.

The American people seem to have a curious paradox about those who occupy the country’s highest office: they want them to be ambitious. Yet on the other hand, they don’t want this ambition to be too naked or too devoid of principles, so that a candidacy seems to be nothing more than a mere power grab. Americans want someone who yearns to be president because they have a vision for the country not because they want to sleep in Lincoln’s bed.

But Bill Clinton was something new even to this old American contradiction, for it is safe to say no one who had occupied the office of President before him had schemed to sit in the Oval Office since he was a teenager, a time when most healthy adolescents are scheming for something more earthy.

Where the Bushes and Kennedys and even Franklin Roosevelt had been seemingly destined for high office by their ambitious families, Bill Clinton’s ambitions were all his own. How a fifteen year-old boy could see his future path so clearly and even more how he could so meticulously plot how to get there is the realm of armchair psychologists, but for those of us whose amateur Freudian analysis extends no further than jokes about a certain cigar, Bill Clinton’s overwhelming ambition seems beyond abnormal.

We all have known high school students with a passion and talent for something—music, math, science, dance, football, acting—who you knew would take that passion somewhere, but even for them it was not so much the where that mattered but the passion. To have a passion for the where makes Bill Clinton a very rare and strange character. Imagine Bill Gates, for example, announcing he was going to start Microsoft or Elvis saying he would be The King or Michael Jordan predicting six NBA rings, that’s how strange Bill Clinton’s passion appears.

The classic story about Bill Clinton's ambition--told even by Bill Clinton himself--concerns his shaking John Kennedy's hand while he was attending Boys' Nation in Washington. What Bill Clinton does not mention is how vigorously he pursued his precious photograph with the President by manipulating his way to the front. In a way the photograph tells the story well, for if you look at it closely you can see an American Legion official with his eyes fixed at that handshake with what can only be described as contempt. Kennedy's face is hidden from the camera, but his body language hardly looks welcoming, for as Clinton leans aggressively into his handshake, Kennedy seems to be leaning in the other direction.

John Kennedy had spoken in his inaugural about "the torch being passed," but little could he realize that the aggressive kid from Arkansas who shook his hand that day would be the one who would grab the torch as aggressively as he grabbed Kennedy's hand and snuff it out. Bill Clinton gripping John Kennedy's hand represents one of the twentieth century's iconic images, for although neither of them knew it at the time, that handshake symbolized the end of the American Century and the values of the Democratic Party that stretched back to William Jennings Bryan. It was a Shakespearean moment, for the man who reached so assertively for JFK's hand would betray the very foundations on which John Kennedy's Presidency stood.

Two decades later the plan to kill Kennedy and the ideals he stood for began with the defeat of Walter Mondale in 1984. A year later a group dominated by conservative Southern Democrats including Al Gore, Chuck Robb, Sam Nunn, John Breaux, and an Arkansas governor named William Jefferson Clinton organized the Democratic Leadership Council (DLC) with the initial mission of securing the 1988 Democratic presidential nomination for a moderate Southerner. The grandfather of this effort was Democrat Gillis Long, a member of the Long family that dominated Louisiana politics, who stated:

Our program amounts to a clean break with the recent rhetoric — but not the traditional values — of the Democratic Party.

In a speech that would salute Bill Clinton and relate the history of the DLC, DLC CEO Al From provided a diagnosis of the illness that the DLC hoped to cure:

As the 1960s passed into the 1970s, the liberal agenda — largely because of its success — ran out of steam, and the intellectual coherence of the New Deal began to dissipate. The Democratic coalition split apart over civil rights, Vietnam, economic change, and culture and values, and the great cause of liberal government that had animated the Democratic Party for three decades degenerated into a collection of special pleaders…Democrats had run out of ideas — and liberalism was in great need of resuscitation.

What From and the DLC would mean by "New Democrat" and "liberalism" would become clearer as Bill Clinton took on a larger role in the DLC leadership. Much as he maneuvered his way to the front row in the White House Rose Garden, by 1990 Bill Clinton had became chair of the DLC. His first act was to preside over the formulation of the 1990 New Orleans Declaration. Although not as well known as Ronald Reagan's 1964 "The Speech," this document would perform the same role for Bill Clinton as Reagan's words for it 15 principles became the blueprint for Clinton's future. The most telling of these principles are:

We believe the Democratic Party’s fundamental mission is to expand opportunity, not government.

We believe that economic growth is the prerequisite to expanding opportunity for everyone. The free market, regulated in the public interest, is the best engine of general prosperity.

This--not Ronald Reagan's famous Inaugural--was the beginning of the end of the American Century and the values of Woodrow Wilson, Franklin Roosevelt, Harry Truman and John Kennedy. The first sentence exemplifies how Bill Clinton came by his nickname "Slick Willie," for, like much else Bill Clinton's seductive voice would utter, it rolls off the tongue easily, but sticks uncomfortably in your mind. The two sentences represent an attempt to weld dissimilar ideas together into some unattainable--and ultimately unstable--compound. They are not so much a political philosophy as forced marriage.

Who can quarrel with expanding opportunity, but just what does reducing government have to do with that? By forcing these two concepts together the phrase implies that shrinking government and the expansion of opportunity have some relationship--something straight from the Gospel According to Reagan.

The second paragraph is more of the same. The first concept is one everyone can agree with; the second is more dubious. A free market "regulated in the public interest" is a contradiction because free markets are not regulated. What these bizarre sentences represent is nothing less than rhetorical alchemy, for the DLC is cleverly trying to bond stock Republican ideas such as "less government," "free markets" with Democratic rhetoric. Much as medieval alchemists sought to bond dissimilar metals or turn lead into gold,the DLC is attempting equally implausible political chemistry. If the American Century proved anything it was that you could not have "expanding opportunity for everyone" in a "free market." Nor could you have "expanded opportunity" and "less government."

The history of Bill Clinton would demonstrate the consequences of this alchemy. Clinton's first moment on the national stage came when he delivered the keynote to the 1988 Democratic National Convention, droning on and on in a performance that can only characterized as embarrassing. Instead of firing up the delegates he put them to sleep. Instead of giving them ringing phrases he read them an encyclopedia. Instead of painting them a compelling vision of the future, he offered the equivalent of a paint-by-numbers scene. He knew it, too, as anyone who relies on their voice knows it. He would not make that mistake again.

Bill Clinton's path to the White House has several significant landmarks that quickly faded into the background only to emerge in 2008 when his wife ran for President. First, Bill Clinton did not win any early primaries outside the South, losing both New Hampshire and Iowa, but he aggressively courted superdelegates the way he grabbed for John Kennedy's hand, so that by the time he won New York, he had a large lead in delegates even though he lacked popular support. This would also characterize his election, in which he won only 43% of the vote in a three candidate race in which maverick Ross Perot siphoned off almost 20% of the vote from incumbent George H.W. Bush.

Clinton did a but better running for his second term, capturing 49% of the popular vote, but still a majority of the American people never supported him. Perot again played the spoiler, although not quite as dramatically as four years before, capturing 8% of the vote to GOP candidate Bob Dole's 40%. Even more troubling, only 49% of America's eligible voters voted, the lowest turnout since 1924. According to Nonvoters: America's No-Shows by by Jack C. Doppelt and Ellen Shearer, 48% of those nonvoters had incomes less than $30,000, only 55% had a high school degree or less, 30% were people of color, and 73% were 18-44 (p. 17) I bring these figures up because they lead to the obvious question of whether the DLC philosophy advanced by Bill Clinton essentially resulted in the disenfranchisement of these voters, who once had been strong Democratic voters.

Certainly 1996, like 1896, has a certain watershed quality for where 1896 is well-known for its uprising of William Jennings Bryan's "commoners," 1996, is less known for essentially ignoring them. The nostalgic vision many Democrats hold today of the Clinton Presidency stresses that it was a time when the Democrats listened to the average American, but the data for that election show otherwise. Some may remember that if the buzzwords for 1992 were "it's the economy stupid," the buzzword of 1996 was "soccer moms."

By the time of his second term, Bill Clinton had developed the belief that his seductive voice could pull him out of any nosedive generated by his push-the-envelope lifestyle. As we all know, he would need it. In a prelude of the scandal that would almost bring down his Presidency, while Clinton was still in high school his next door neighbor and girlfriend Carolyn Yeldell saw him kissing someone else.

I walked out my back door and up the front walk to Bill's front door--and saw Bill and Sharon through the window. They were standing embraced in a major kiss near the table. It was the classic moment, right before I was going to ring the bell. (Maraniss, p. 117)

Yeldell gave up romantic designs on Clinton when she decided he would never be faithful, yet that seductive voice worked so well she remains one of his close friends.

Then there was the issue of Bill Clinton's never-to-be-untangled dodging of the draft. The story has so many twists and the evidence has become so tainted that it would take a book to tell the entire story. Again, the seductive voice worked so well that no one to this day can say for sure what happened.

When he became the boy-governor of Arkansas, Bill Clinton went down to defeat after one term, dogged by a decision to raise license plate fees. At that point Bill Clinton appeared destined to become the political equivalent of a one-hit wonder who faded back into obscurity as the law professor he had been before charging into politics. But the person who pushed his way to the front of the crowd to have his picture taken with John F. Kennedy and who had plotted a path to the White House at a time most boys are learning to shave was not about to go quietly.

Again, he placed his future in that seductive voice. As it had bailed him out with Yeldell and the draft, it would again work its magic. This time the vehicle still stands as one of America's most clever pieces of political strategy, for what Bill Clinton decided to do on the advice of his aides, was to deliver a speech asking the people to forgive him for the mistakes of his first term. He won, largely because that seductive voice convinced Arkansas voters he would not be a bad boy again. The basic pattern of Bill Clinton's life had been set.

From the perspective of transformational leadership it is instructive to compare Bill Clinton's use if his rhetorical powers with those of the Democratic leaders who defined the American Century. William Jennings Bryan, Woodrow Wilson, Franklin Roosevelt, and Harry Truman all placed their voices in service of a higher cause. With each of them, their voices became the embodiment of principles along with embodying the four dimensions of transformational leadership identified by Bernard Bass: individualized consideration, idealized influence, intellectual stimulation, and inspirational motivation.

For Bill Clinton, on the other hand, his voice was always a tool of manipulation, a transactional means to an end rather than a transformational expression of values. Bill Clinton came to rely on his voice to get him out of trouble as much as he did to define what James MacGregor Burns termed "end values such as liberty, justice, equality." In this, Clinton's voice was as much a defensive as an offensive weapon. With each miraculous recovery, Bill Clinton came to believe his voice could talk people out of anything.

Bill Clinton's Second Inaugural is not a great speech but it is a significant one. It has a portentous tone that a decade later has it walking the fine line between self-promotion and self-parody that marked so much of Bill Clinton's life. It is also one of the strangest inaugurals in American history, a speech that reflects a time when politicians so nakedly aspired to greatness it now seems a national embarrassment.

No two leaders better personified this than Bill Clinton and his arch-enemy Newt Gingrich. The two represented mirror images of the other, for each thought himself the smartest leader of his times and an epochal figure destined to remake his political party and the nation. Both of them wanted to be the Franklin Roosevelt of the new millennium. Gingrich's Contract with America drips with the rhetoric of self-importance beginning with its pretentious preamble that brazenly evokes both Abraham Lincoln and God.

Like Lincoln, our first Republican president, we intend to act ‘with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right.

This is rhetoric run amuck, much like Gingrich's leadership. In his Second Inaugural, Bill Clinton would show he could be just as pretentious.

We will see how pretentious in Part Two.

Labels: Ralph Brauer

So far, I have to say I find this argument against Clinton unconvincing, particularly in its list of "good" presidents.

Idolizing Kennedy is something people do subjectively. Objectively, I don't see that his record is a testament to promoting democracy and justice. He gave the go-ahead to overthrow Diem in South Vietnam, and to overthrow Kassem in Iraq--and also helping to install and support the Baath party, which launched a bloodbath against all who opposed it. He stonewalled the Civil Rights Act. And before he was president, he refused to censure Joe McCarthy.

And if we're lambasting Clinton for infidelity, choosing Kennedy to stand as the good opposite of Clinton is odd.

Another "good" president listed in the article is Woodrow Wilson, a toxic racist who thought the system of checks and balances was a "grievous mistake."

The very fact that from a young age Clinton wanted to be president seems to be intolerable to the author, but I can't see that this ambition is in itself a negative. A lot of psychologizing is done on the photo of Clinton with Kennedy. I find it hard to believe that Bill Clinton is the only person in history to be eager to shake hands with a president.

I'll look with interest for part II of this series, but so far the major claims against Clinton seem to be that he wanted to be president, that he was a talented orator, and that he was personally dishonest. So far, that could name a number of presidents, but none of them are being charged with destroying democracy in America.