During my research for The Strange Death of Liberal America, I explored the records of the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission, using them as the centerpiece for a chapter on Fannie Lou Hamer. In honor of Martin Luther King Day, I returned again to those records to research what they had to say about Dr. King.

In 1956, in response to the Brown Decision, the Mississippi legislature approved the creation of the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission "to do and perform any and all acts and things deemed necessary and proper to protect the sovereignty of the State of Mississippi, and her sister states, from encroachment thereon by the federal government or any branch, department or agency thereof."

Commission records lay under a tombstone of secrecy and protection until a lawsuit by the American Civil Liberties Union opened them for the public. Although the records appeared sanitized, what emerged was shocking enough—ghosts whose wails tell a sordid story. The handwritten records from one county show payments to informers ranging from $25 up to almost $100, with $40 not being uncommon. Check marks march down the page, marking African American informers, sometimes several for the same family. Like Nazi and gulag administrators, the Commission believed nothing was too inconsequential to report. An eerie 1964 memo notes: "Rita Schwerner [the wife of slain Civil Rights worker Michael Schwerner] recently purchased a Singer sewing machine in Meridian and had it delivered to 2505 1/2 5th Street in Meridian."

To picture Mississippi at that time you have to be prepared to walk into a fevered nightmare which periodically reasserts itself into our consciousness. Fantastical images and shapes flit in the darkness, and curses and screams come from beyond the edge of safety and sanity. We awake with that uncomfortable feeling of sorting out what is real. One memo captures the atmosphere: "It was pointed out to Shiboh by the writer," it notes, "that he was going a bit beyond the tutoring in Leland and he was advised to be very careful he did not go beyond the provisions of the law and create a problem which could bring about serious trouble."

The Sovereignty Commission recorded over a thousand entries on the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, jr. They range from newspaper clippings to the memos of agents the Commission had infiltrating organizations, churches, and communities. They testify to the almost paranoid fear the racists had for the power of Dr. King as well as the extent the Sovereignty Commission penetrated into every area of life in Mississippi.

America still has yet to properly confront this dark side of its history when a state government ran the equivalent of a secret police force every bit as evil as those on the other side of the Iron Curtain. Only by understanding this atmosphere can we truly appreciate the vision and courage of Dr. King and of millions who resonated with his message and brought this country from darkness to a time when a black man could make a serious run for the Presidency.

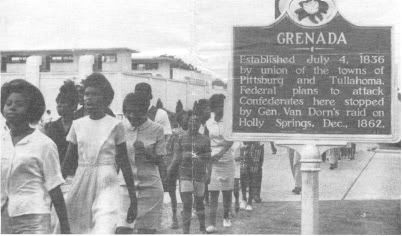

All of this is on exhibit in memos written by agents detailing the Sovereignty Commission's attempts to deal with the Grenada County Freedom Movement (GCFM). The GCFM represented one of those local uprisings that testify to the determination and bravery of hundreds of African Americans who fought against the Sovereignty Commission and its secret police force.

Grenada County was one of the dark hearts of the old Confederacy. During Reconstruction, four African American men were lynched there on one day. By the 1960s, the county had become a symbol of Southern intransigence, a place where both sides knew what was at stake.

Bruce Hartford, an organizer with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference described the significance of Grenada in an oral history interview:

Grenada hasn't gotten a lot of publicity, there was no big law that came out of it, but the Grenada movement was very heavy. The Grenada movement probably lasted longer, in terms of the upswelling of people's mass activity, than any of the other mass movements. Longer than Birmingham, longer than Selma, Albany, St. Augustine, Natchez. I mean lasting longer in terms of how long people kept mass direct-action going.

Perhaps the most notorious event of the Grenada Movement occurred when a Klan mob with clubs, ax handles and chains ambushed elementary school children who were walking through town to enroll in a school that had been ordered to desegregate. Hartford remembered the atmosphere in Grenada:

Grenada became so intense at times that when SCLC field staff who had led demonstrations in places like St. Augustine — which was also very heavy — came to Grenada, they were taken aback. One guy — I won't call his name — the first demonstration he was assigned to lead in Grenada he saw the mob and he turned us around.

Hartford described Dr. King's role in the movement:

Dr. King gave a speech and the people in Grenada had told him, "We're ready to move. Are you gonna stay and move with us?" And he said, "No, we have to finish this Meredith March, but as soon as it's over, we will come back."

And come back they did, precipitating a major crisis for Mississippi. Excerpts from a letter by agent Erle Johnston, jr. detail the strategies the Commission employed.

We have attempted, by direct contact and through infiltration, to determine whether the native negroes are in any mood to disregard Dr. Martin Luther King and any of his aides.

The letter goes on to report how the Commission prepared a radio address for the mayor (remember this is America and here is a secret police force writing speeches for the local mayor, speeches which I am sure he was in no position to refuse). Johnston also notes the Commission purchased 3,000 "think Grenada First!" buttons at a cost of $114.

I advised Allen that he and other Negroes in Grenada County should get busy and put the brakes on Dr. King and his movement.

Imagine for a moment what must have been going through Allen's mind. A man identifying himself as an agent of the government of Mississippi has asked you to "put the brakes on Dr. King." The agent did not need to threaten, for in a police state where people like Michael Schwerner disappeared and others were beaten and harassed no threats were needed. Instead, the agent merely let Allen fill in the blanks with his own nightmares. The "put the brakes on" phrase is especially eerie, given that Dr. King only had less than eighteen months left to live.

A memo by agent Tom Scarbrough reports on a speech by Dr. King:

Dr. King spoke to a large group of negroes at the New Hope Negro Church. He complimented them highly in carrying out his demands on the city of Grenada, and in the course of his talk pledged that Grenada would be further invaded until their demands were met.

This paragraph reeks with the prejudices held by many segregationists at the time--and by some Americans still. Note how the memo paints a picture of the Grenada Movement as fed by "outsiders" and King himself as a dictator who told people what to do. Most of all, note the none-too-subtle characterization of local African Americans as passive followers. Contrast this with the picture painted by Bruce Hartford.

This paragraph in an obscure memo written by a Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission member in 1966 testifies to the impact that Dr. King had on not only Grenada but America. It also testifies to an image of Dr. King that unfortunately still persists.

As with many great historical figures, there are many Dr. Kings that coexist uneasily in the American mind, some acknowledged and some hidden, but still powerful. There is, of course, the Dr. King celebrated on the holiday named after him--the inspirational leader of The Speech. There is Dr. King, the political leader of the Montgomery Bus Boycott and other events. There is Dr. King the tactician of nonviolence. There is also the Dr. King of agent Scarbrough's memo and Johnston's letter.

To the Scarbroughs and Johnstons of the world, Dr. King was little more than a demagogue who gave orders and expected them to be carried out. Johnston's memo also speaks of "King and his movement." Few people today would openly admit to this view, so it has been replaced by another more insidious picture which views the Civil Rights Movement in the traditional image of leaders and followers. Contrary to Scarbrough's memo, the picture that emerges from the Sovereignty Commission records is of what can only be termed a collaborative movement.

In a moving passage, Harford described the power of the nonviolence and the collective effort that lay at the center of Dr. King's work:

I saw us do non-violent things in Grenada that to this day are just unbelievable to me. There were times we had this march of two or three hundred people circling the square, and surrounding us were a mob of 500 Klansmen. But some of the time — not always — we could literally hold them off by the quality of our singing. We could create a psychic wall that they could not breach, even though they wanted to. And on those times when they did attack, our non-violent response minimized their injuries to us.

A demagogue cannot conduct a nonviolent movement. Nonviolent movements are not "his" movements, because when you are lying on the ground being beaten like the Klan beat Hartford you do not endure that beating for a "his." Nonviolence by its very nature transcends the easy categories we have for leaders and the sometimes simplistic ways we view leadership. The story of Dr. King and the Civil Rights Movement is much more complex than the platitudes that flow too easily on this day.

When James McGregor Burns coined the term transformational leadership, he could well have been describing Dr. King:

Transformational leadership is more concerned with end-values, such as liberty, justice, equality. Transforming leaders “raise” their followers up through levels of morality, though insufficient attention to means can corrupt ends… The test of leadership function is their contribution to change measured by purpose drawn from collective motives and values.

But even this fails to capture it all. What the definition misses is the give-and-take, and, yes, the disagreements, that were part of the struggle for Civil Rights. Fannie Lou Hamer, for example, deeply resented what she felt were the class and gender prejudices of many Civil Rights leaders. In the end, Dr. King was special not because of 1what he led, but what he followed.

That is important in understanding the place of the Grenada Movement. When it was "over," Hartford wrote:

The names of other courageous African Americans, some forgotten, some remembered, lie in the Sovereignty Commission files along with the name of Dr. King. We do them and Dr. King a disservice by failing to also recognize them. The Grenada Movement involved an estimated 700 people at its height. As Hartford points out, it resulted in no major legislation; it only changed a community, a state and a nation forever. All of those involved taught us that with each generation, each community, and, yes, each election we must continue to fight for true equality, for a true level playing field.Over the following weeks and months, there are few demonstrations but the Grenada County Freedom Movement digs in for the long haul — organizing, mounting legal defense for those arrested, and continuing voter registration and political organization. Harassment of the Negro students in the white schools continues, but at a lower and more subtle level. By the end of the school year additional Negro students had been forced out, but Grenada still had the more Negroes attending formerly white schools than any other rural Mississippi county.

Labels: Ralph Brauer

I didn't get a chance to comment on this when it was fresh (buried in grading, unfortunately) but I wanted to mention how much I enjoyed it. Your chapter on Fannie Lou Hamer was, in my opinion, the best in your book, and this is a fabulous addition. Kudos for the mention of Burns' book, too, which is very important to my current research.

Thank you, Ralph, for this moving look into a part of King's history and the Civil Rights history I knew nothing about. I was particularly moved by the reference to the barrier created by their singing.

I wish more people in this time could experience the power that comes from standing together. I've been watching the stories from the sixties about the firehoses, the dogs. It did indeed take a strong moral center and the belief that they deserved better, and the willingness to literally put their lives on the line to make life better for themselves and their children, the likes of which we haven't seen since.

Thanks. This was the most interesting story about King I've read yet on this anniversary, and I've been looking!