Ronald Reagan's First Inaugural is justly regarded as one of America's greatest speeches. It is also one of the most misunderstood. Like many great speeches it is a tangle of paradoxes, some of which we are still puzzling over. Those paradoxes all begin with the voice.

When is a voice no longer a voice, but something else, something coached, well-trained and practiced so it becomes not so much a voice but a mirror, its vowels and consonants referring not so much to the speaker but the listener, so that each person who hears it hears something from deep in the recesses of their own mind.

In the electronic age, this has become the new ideal, perhaps because the artifice of microphones and sound boards demands it. Once we wanted our politician’s voices to reflect them, now we want them to reflect us, for artifice forces us to search the ether for authenticity and the only judge we have of that lies in the sound studios of our own minds.

Perhaps no one epitomizes this more than Ronald Wilson Reagan. To listen to his voice is to be drawn even against your will into the sonic equivalent of soft focus. Something in the tone that can move effortlessly from a whisper-like confessional to an earnestness that seems to come from somewhere deep in the chest like a war cry, wins audiences over in the way that a master guitarist can summon so many emotions from six simple strings.

Ronald Reagan would make full use of those skills in the 1964 Presidential campaign. The ostensible title given the address was “A Time for Choosing,” but to Republicans and others it has since been known simply as "The Speech." Fittingly, it was not delivered on the floor of one of those wooden-raftered caverns with a name like The Wigwam or an immense amphitheater like Madison Square Garden, but from inside the little glowing box that had become a fixture in America’s living rooms. The wooden benches that had served as the galleries in political conventions of the past had been replaced by armchairs in people’s homes. It is also fitting that Reagan’s speech was part of a paid, prerecorded television commercial. It was a perfect setting for Reagan the actor.

In terms of its significance, “The Speech” deserves to be regarded with the “Cross of Gold” and a handful of other speeches that have not only electrified a campaign, but also defined the future of a political party. Columnist David Broder knew what he was witnessing, for he termed “The Speech:”

The most successful political debut since William Jennings Bryan electrified the 1896 Democratic Convention with the "Cross of Gold” speech.Rarely are people swept away with waves of words. In the nineteenth century of “Cross of Gold” a significant percentage of Americans had heard enough stump speeches to qualify as experienced judges of their quality. In the twentieth century with radio and television lending politics all the stage-managed characteristics of a Hollywood movie, audiences have developed a more jaundiced attitude toward both speech and speaker.

But in 1964, the kind of speech Ronald Reagan recited was something relatively new. Most candidates had managed the transition to the new medium of television with the same trepidation Hollywood stars had managed the transition from silents to talkies. Speaking to a camera was a new skill for most of politicians, one that required many more significant changes than the transition from speaking to crowds to speaking over the radio. You had to learn how to modulate your voice, how to move your head so it did not appear wooden, how to look into the camera as if you were looking into the eyes of an unconvinced voter, and—as Richard Nixon learned in 1960—even such unpolitical skills as the art of makeup.

Ronald Reagan knew all these things. His best performances as an actor had been delivering heart-felt “values” speeches such as the one he gave as the dying Gipper in Knute Rockne, All-American. Yet for all this background, Ronald Reagan was a washed-up movie actor when he delivered “The Speech.” After his Hollywood career had turned sour he had been fortunate to find work with General Electric in 1954 serving as host for G.E. Theater, a now extinct programming genre which presented adaptations of popular plays, short stories, novels, magazine fiction and motion pictures. It was a role that certainly was a step down for the former sidekick of Errol Flynn, for all it required of the actor who once hungered for dramatic parts like that of the doomed George Gipp was that he read what are known as the “ins” and “outs,” introducing each week’s program and then signing off at the end.

He might have perished there were it not for the second part of the GE job which required him to barnstorm the country as the company’s goodwill ambassador. To Reagan’s credit, unlike other stars who might have sleepwalked through these functions, Ronald Reagan threw himself into his new role and in doing so found his true calling. Like actors who polish their skills in little theaters in small towns, Reagan honed his speaking skills at GE meetings, factory tours and appearances before local gatherings.

Reagan also found his voice, learning that Hollywood role playing could be placed in the service of delivering a political message. Instead of handing him a packaged script, GE, as people would later say, “let Reagan be Reagan.” So he gave full vent to the fanatical anti-communism that had characterized his reign as head of the Screen Actor’s Guild. Eventually Reagan became so good at what he was doing that his conservative opinions caused GE to let him go, fearing the corporation would be tainted as favoring right wing causes.

When it came time for Reagan to deliver “The Speech” he had been well-rehearsed. He also had the aid of several people, foremost of whom was his wife, the former Nancy Davis, a mediocre actress and the daughter of Chicago neurosurgeon Dr. Loyal Davis. Reagan had married Nancy Davis after his marriage with Jane Wyman went sour, in part because of his obsession with the Screen Actor’s Guild. Unlike Wyman, Nancy Reagan not only supported her husband’s conservatism, she had far bigger and different dreams for him.

"The Speech" would help propel her husband on his way to making those dreams real. Delivered in support of Barry Goldwater it showed he made a better Goldwater than Goldwater himself. Although Goldwater would be resoundingly trounced, "The Speech" would rise like one of those movie heroes who picks up a fallen banner and leads the troops to victory. It captured all the pent-up grievances of those on the right who had come to resent the Great Society and what they felt were the appeasement of the left toward the Soviet Union.

Officially titled "A Time for Choosing," "The Speech" contained many of the rhetorical elements that would become Reagan staples: the use of anecdotes and selective statistics to drive home a point, the rapier-like turns of phrase that skewered his opponents while bringing smiles to his supporters, the "common sense" logic that sounds good when you hear it and for which you can offer no counterargument without a great deal of research, and, of course, the almost messianic belief that there is only one way to interpret the Constitution and American history.

All these tactics were perfect for the immediacy of television where each viewer sits alone in the living room, their minds directly linked to the speaker's words like some Vulcan mind meld. In "The Speech" Reagan opens by referring to his switch from the Democrats to the Republicans--a move he officially made two years before.

I have spent most of my life as a Democrat. I recently have seen fit to follow another course.Then he goes after the GOP's favorite target--taxes--in his third paragraph, saying:

No nation in history has ever survived a tax burden that reached a third of its national income.

After a brief recitation of the issues of war and peace comes the paragraph that some conservatives can still recite from memory:

If we lose freedom here, there is no place to escape to. This is the last stand on Earth. And this idea that government is beholden to the people, that it has no other source of power except to sovereign people, is still the newest and most unique idea in all the long history of man's relation to man. This is the issue of this election. Whether we believe in our capacity for self-government or whether we abandon the American revolution and confess that a little intellectual elite in a far-distant capital can plan our lives for us better than we can plan them ourselves.The remainder of the speech has examples from the farm economy and a long discussion of welfare and urban renewal programs that was to become the center of what would become the Republican Counterrevolution against the New Deal. Amidst all the recitations of welfare's shortcomings, Ronald Reagan raises the questions that America has struggled to answer over the last half century:

Well, now, if government planning and welfare had the answer and they've had almost 30 years of it, shouldn't we expect government to almost read the score to us once in a while? Shouldn't they be telling us about the decline each year in the number of people needing help? The reduction in the need for public housing?This is a masterful paragraph. The rhetorical tactic of raising a question and leaving it unanswered has a long history, in part because it lets the readers fill in the blanks with their own answers. Reagan begins with a question that all but implies a "yes," especially because of the folksy way he frames it. Behind it lies the entire Counterrevolutionary doctrine of "accountability" that spawned measures like No Child Left Behind.

The implication behind the next two questions lies in an assumption that at some point people will not need government aid. We know that isn't true, there will always be people who, for whatever reason, illness, injury, disability, the economy, lack of skills, or just plain bad luck will need help. For Republicans who still believed in William Graham Sumner's "survival of the fittest," this question also had to have resonated with their own belief that the poor are responsible for their own bad luck.

If Reagan's questions raise uncomfortable issues, sprinkled in his discussions of them are classic Reaganisms that his audiences would later come to expect, but at the time must have pulled more than a few people out of their seats and onto their feet:

Well, I for one resent it when a representative of the people refers to you and me--the free man and woman of this country--as "the masses." This is a term we haven't applied to ourselves in America.When you read them, these phrases have a certain in-your-face edge to them that even today is unusual for a political speech, yet delivered in Reagan's practiced voice the edge seems smoother, almost folksy so you are caught off guard. The former actor and GE spokesperson had learned his craft well.

A government can't control the economy without controlling people.

In a program that takes for the needy and gives to the greedy, we see such spectacles as in Cleveland, Ohio, a million-and-a-half-dollar building completed only three years ago must be destroyed to make way for what government officials call a "more compatible use of the land."

Well, the trouble with our liberal friends is not that they are ignorant, but that they know so much that isn't so.Actually, a government bureau is the nearest thing to eternal life we'll ever see on this Earth.

Those who would trade our freedom for the soup kitchen of the welfare state have told us that they have a utopian solution of peace without victory.

These skills would come together in the famous closing of "The Speech" in which he appropriates one of Franklin Roosevelt's most memorable phrases for Goldwater, his audacity a rhetorical symbol of the Counterrevolution's intent to undo the New Deal:

You and I have a rendezvous with destiny. We will preserve for our children this, the last best hope of man on Earth, or we will sentence them to take the last step into a thousand years of darkness.It would be almost two decades before "The Speech" would come to full fruition. Reagan would become Governor of California, challenge Gerald Ford for the Republican nomination in 1976 and finally win the Presidency in 1980. There is little question those who had first heard the speech and seen the speaker as a future president played a large role in that ascent.

When Reagan began planning for his inaugural address it seems appropriate that he would tell speech writer Ken Khachigian to use "The Speech" as a template. The use of Khachigian raises a long-standing question about Ronald Reagan. For some time, it was fashionable to wonder if Reagan really wrote his speeches or if he was just reading another script handed to him.

Recent books and studies have shown us that Reagan was extremely intelligent and that he did a great deal of his own writing. Reagan in His Own Hand details the radio addresses Reagan himself wrote between 1975 and 1979 to keep himself in the public eye. It shows a writer with a keen sense of language and a rare ability to make complex ideas understandable. Ronald Reagan was no Woodrow Wilson--he would probably be the first to concede that--but neither was he the empty-headed script reader portrayed by his enemies.

In what is probably the best biography of Reagan, Reagan's America, Garry Wills brilliantly draws attention to how Reagan purposely made mistakes in his speeches:

Reagan has often goofed to look more natural--broken the grammar of sentences, feigned embarrassment, professionally avoided the appearance of being a professional. It is an important art in democratic politics. [p. 193]

With the First Inaugural--as with "The Speech"-it is clear the effort was Reagan's. Much as Harry Truman took his advisor's ideas and even some of their phrasing and then delivered his Kiel auditorium speech off the cuff, Reagan took Khachigian's drafts and then rewrote the final speech himself. No source, pro- or anti-Reagan disputes this. Richard Reeves probably has the best portrait of the writing of the speech in President Reagan: A Triumph of the Imagination. He outlines how Reagan gave Khachigian a six-inch stack of 3x5 note cards that held the best lines of his previous speeches. In a discussion with Khachigian he also sketched out a broad outline of the speech:

The system: everything we need is here. It is the people. This ceremony itself is evidence that government belongs to the people....Under that system: our nation went from peace to war on a single morning, we had the depression etc....We showed that they, the people, have all the power to solve things....Want optimism and hope, but not "goody-goody."...There's no reason not to believe that we have the answer to things that are wrong. [p. 4]

But Reeves goes on to acknowledge:

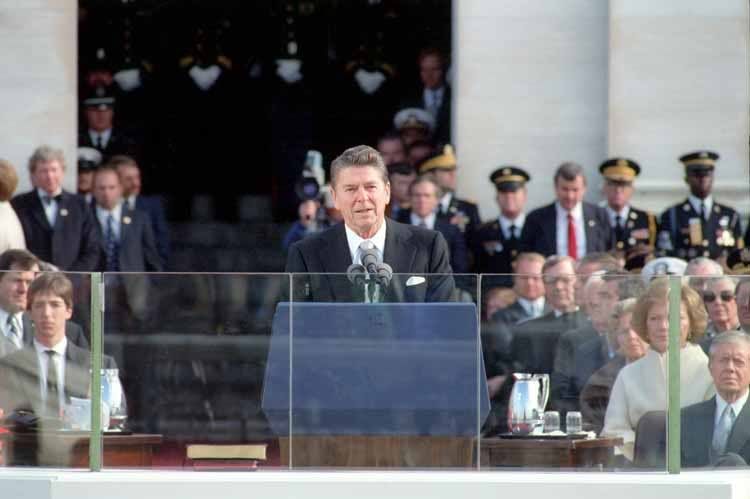

The words were Reagan's own. He wrote the final version of the speech out in longhand on a yellow legal pad. (p. 5)Reagan made an unusual choice about the location for the speech. Where other presidents had addressed the nation from the front on the Capitol, Reagan chose to use rear, which as millions of tourists know provides one of the most famous views in America as it looks down the mall towards the Washington Monument, Lincoln Memorial, and Jefferson Memorial and now the World War II Memorial. Across the river lies Arlington National Cemetery. There seems little question Reagan personally stage-managed this setting which he would invoke in his Inaugural Address.

Like a combination of political advance men and school teachers, Reagan's staff spent the days before the speech lecturing to the media about the importance of this view, using language they might have cribbed from a Hollywood Western or one the nineteenth-century handbills that circulated across the Atlantic enticing new immigrants. The rear of the Capitol, they reminded the reporters, looked to the West which to Americans had always symbolized the boundless manifest destinies of opportunity.

Reagan's Inaugural begins with a brief recitation of the importance of the "orderly transfer of authority," but then does something quite extraordinary in singling out his predecessor for his help during the transition. Perhaps this was to help soften the blow of what would follow, which indicts Jimmy Carter's leadership:

By your gracious cooperation in the transition process, you have shown a watching world that we are a united people pledged to maintaining a political system which guarantees individual liberty to a greater degree than any other, and I thank you and your people for all your help in maintaining the continuity which is the bulwark of our republic.The man who could brilliantly write two-sentence teasers for his radio addresses (Reagan would have made a great blogger), then gets right to the point--the economy, noting the nation was suffering from one of longest inflations in history. His detailing of the consequences of that inflation allows him to make one of the clever rhetorical transitions that characterized so many Reagan speeches, moving directly from inflation to his long-time causes of taxes and government spending:

Those who do work are denied a fair return for their labor by a tax system which penalizes successful achievement and keeps us from maintaining full productivityThen comes the paragraph that is probably the most quoted portion of this speech:

But great as our tax burden is, it has not kept pace with public spending.

In this present crisis, government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.What is often omitted, though, is the final sentence of this paragraph:

The solutions we seek must be equitable, with no one group singled out to pay a higher price.This sentence along with several others remains one of the paradoxes of Reagan's Inaugural.

Labels: Ralph Brauer

Isn't it weird that this celebration of a bullshit speech by one of the most shameless bullshitters in the history of bullshit only draws one critical comment?

Reagan keeps talking about a "crisis" that can be solved by less government, and the only crisis in 1980 was the Iran hostage crisis where Reagan and Khomeini cooperated to make Jimmy Carter look as bad as possible. Less government would have helped... how?

The senile tool of the zillionaire class, Reagan, had acquired a low-rent folksy persona as a TV host and it was good enough for a whole lot of white people who were willing to believe anything that promised lower taxes. Please God let us contribute absolutely nothing to the nation!

Reagan's constituency had all the dignity of tapeworms... parasites who wanted a free ride with their little nest-eggs in odd lots of common stock that would pay them collectively less than the mountain of debt Reagan shoved onto the next generation.

So this moron pandering to a parasite class isn't so much a "paradox," as the author of this article wants us to believe... Reagan and his clientele of thieves and parasites are more like a disgrace than a paradox, and it's equally disgraceful that the community of historians has been so forgiving to this miserable front-man that the current crop of Republican candidates can invoke his name as if it stood for something besides greed and irresponsibility.

Unknown on 12/30/2007 2:22 AM:

Jacob, I'll remind you that it's possible for a politician to be a great speechifier but a terrible leader. I don't know many historians who think Reagan was a great President, but few can deny with a straight face the incredible power of his public speechmaking and persona. I applaud Ralph for emphasizing the distinction.

"You and I have a rendezvous with destiny."

Harharharhar!!!

Jeremy Young apparently thinks that's part of a great speech!

What would imbecilic high-school rhetoric look like, Jeremy, if that garbage is a great speech?

Reagan is the poster-geezer of the parasite class, and they would have elected him for snorting like a pig! "So what if he farts instead of talking... We want a tax break!"

Reagan was President of the Republic of Tape-Worms, and all they really cared about was sucking as much juice out of the guts of America as possible, and returning nothing!

"You and I have a rendezvous with destiny." The suckers who voted for Reagan had a rendezvous with nickels and dimes, and that was all it took to buy their votes, while Reagan's zillionaire puppet-masters like Donald Reagan fed the senile old monkey canned speeches that wouldn't have fooled the village idiot way back when the USA was still a nation instead of just another collection of boobs and hustlers. The boobs pretended to believe the bullshit so they could save their nickels and dimes, and the hustlers pulled the strings on their senile puppet and got infinitely richer than any other gang in the history of crime.

"The paradox of Ronald reagan?" What next? "The paradox of McDonalds?"

Idiots bought Reagan's message because it was cheap. Save your nickels and dimes from the tax-bogeyman! You think he could have sold that shit if it came with a price?

It's like claiming a Big Mac has something to recommend it besides grease-and-sugar cheapness. But they don't sell a $50 knock-off of the grease-and-dogmeat Big Mac at La Tour d'Argent, because nobody eats those shit-burgers who can afford anything better.

Likewise you couldn't sell Reagan's shit-burger message except to nickel-and-dime shit-eaters, and once you brought Southern racists into the coalition, and saturated the corporate media with the same shit message 24/7, you had enough votes to elect the senile monkey Reagan, and the same coalition would have voted for a real shit-burger, literally a grease-blob in a bun, if you stuck the same message on it with a post-it note, and somehow got it on the ballot.

Instead of incomprehensible "appreciations" of the senile sock puppet's speeches, maybe it would be more useful to make a video of the firefighters running into the burning WTC on 9/11 with a voice-over from Ronald Reagan saying “The most terrifying words in the English language are: I’m from the government and I’m here to help.”

Tell it to the firefighters, from your perch in Hell, you shameless old ass-monkey!

Jeremy Young can't think of a way to make Reagan sound like anything except a senile ass-monkey whose message was bought by a nickel-and-dime parasite class hypnotized by its own greed, so he resorts to personal insults.

Why don't you answer the question instead, Jeremy?

How does Reagan's wisecrack about help from the government play as a voice-over of the firefighters running into the burning WTC? Are these government employees the same people Reagan claimed were destroying the United States? Are the firefighters who gave their lives trying to save other people really the enemy?

Or was Reagan's "message" just brain-dead bullshit from beginning to end? Did anyone ever believe it, or was it just a front for racists and greedy little stock owners with 47 shares of common stock, who were willing to sell out the nation for nickels and dimes?

Maybe you can also commission an article about "The Paradox of Rush Limbaugh," who peddles the same ridiculous garbage to the same ridiculous parasites.

"Anything you say, Rush, as long as it saves us a few nickels and dimes!"

It doesn't take a "Great Communicator" to make those tape-worms salivate for their pitiful payoff.

Reagan's rhetoric was good enough for piggy-bank tax-rebels who had already forgotten the Great Depression, and it was good enough for racists who wanted to forget Brown v. Board of Education, and it was good enough for zillionaires who could read the enormous pay-off between the lines, and you can probably sell a comparison to William Jennings Bryan to readers who don't know the banks hated Bryan as much as they loved Reagan, so let's put it all together and celebrate the senile supporting actor who was such an endearing frontman for racism and upward re-distribution of wealth.

Hurrah!