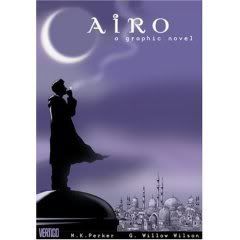

G. Willow Wilson is a blogfriend of mine who used to post at Eteraz.org. She's just published her first book, a graphic novel titled Cairo ($16.49 at Amazon; hardcover, 160pp), which is illustrated by M. K. Perker. While I have some constructive criticisms of the work (which I'll get to a bit later), I want to emphasize right up front that Cairo is a fabulous read that is well worth picking up, particularly if you have an interest in fantasy literature and/or the Middle East peace process.

G. Willow Wilson is a blogfriend of mine who used to post at Eteraz.org. She's just published her first book, a graphic novel titled Cairo ($16.49 at Amazon; hardcover, 160pp), which is illustrated by M. K. Perker. While I have some constructive criticisms of the work (which I'll get to a bit later), I want to emphasize right up front that Cairo is a fabulous read that is well worth picking up, particularly if you have an interest in fantasy literature and/or the Middle East peace process.The story begins with Ashraf, an Egyptian drug-runner, as he attempts to dispose of a hookah he collected from the lair of a drug lord. Only after he pawns the item to an American traveler, however, does he discover that it's a magic hookah, and that if he doesn't get it back, very bad things could happen to people he cares about. What follows is a delightful romp through the streets of Cairo, deep into the Pyramids, and in the subterranean world of the Undernile. Along the way, we encounter a cast of zany and personality-filled characters including an out-of-luck genie, a would-be suicide bomber, a naive American journalist (modeled, perhaps, on Wilson herself), and a tough-yet-fragile female Israeli soldier.

Before I talk about Wilson's writing, I should mention the artwork, because it is mind-blowingly outstanding. Perker's style is based in well-worn comic-book traditions -- his depictions of demons and the evil drug lord could come right out of old Spiderman comics -- but he adds outstanding visual techniques that draw the reader forcefully into the action of the story. A few examples are his use of shifting perspectives -- at times we appear to be looking through the eyes of some of the characters, as when we watch a female character's feet while she removes her veil -- and his technique of building two sequential frames around a single drawing of an individual, which gives the impression that the reader is revolving around the character to see the entirety of the action. Beyond these tricks, Perker's vivid illustrations make the reader feel as if he is actually in the streets of Cairo, a real thrill for those who, like me, have never visited the Middle East. My only quibble with Perker is in his depiction of Tova, the Israeli soldier; his attempt at rendering ethnically Jewish features often makes the character look ugly rather than distinctive.

Before I talk about Wilson's writing, I should mention the artwork, because it is mind-blowingly outstanding. Perker's style is based in well-worn comic-book traditions -- his depictions of demons and the evil drug lord could come right out of old Spiderman comics -- but he adds outstanding visual techniques that draw the reader forcefully into the action of the story. A few examples are his use of shifting perspectives -- at times we appear to be looking through the eyes of some of the characters, as when we watch a female character's feet while she removes her veil -- and his technique of building two sequential frames around a single drawing of an individual, which gives the impression that the reader is revolving around the character to see the entirety of the action. Beyond these tricks, Perker's vivid illustrations make the reader feel as if he is actually in the streets of Cairo, a real thrill for those who, like me, have never visited the Middle East. My only quibble with Perker is in his depiction of Tova, the Israeli soldier; his attempt at rendering ethnically Jewish features often makes the character look ugly rather than distinctive.Against this vivid backdrop, Wilson spins a memorable tale of magical battles and human interactions. Her fertile imagination and whimsical wit imbues all the characters with an infectious spirit which renders them at once believable and three-dimensional. None is more astutely portrayed than Ashraf, whose brusque, street-smart persona masks a humanity and leadership ability that is eventually revealed in the late pages of the book. Ashraf is the fulfillment of every writer's dream: a fully-drawn, completely realistic character who undergoes a persuasive transformation and brings the reader right along with him. Not all of Cairo's characters attain this exalted brilliance (again, Tova in particular seems somewhat caricatured to me), but all are still impressive and very endearing. In fact, the book is probably most notable for how memorable its characters are and how human and likable they seem even to the skeptical reader; as a moderate supporter of Israel politically, I didn't expect to enjoy characters like Ashraf and his friend Ali, a Caironese alternative newspaper publisher, as much as I did, nor did I anticipate having these figures and their interactions stick in my head for days after reading Cairo.

In addition to her memorable characters, Wilson also excels at creating a narrative out of a mixture of fantasy, mythology, and documentary-like reality. Imagine a cross between Brian Jacques' Redwall, Joss Whedon's "Firefly," and the Indian film Monsoon Wedding, and you've got a general picture of the sort of off-the-wall storytelling Wilson is doing here. Unlike fantastical elements in many fantasy-inflected works, the genies and demons in Cairo don't seem at all out of place in the realistic world of drug-runners and border guards in which the story takes place. Instead, they both add to the exoticism of the setting and provide Wilson with a shrewd way of getting at the higher motivations of the hard-bitten realists the novel portrays. Wilson's hit on an excellent strategy here: myths and religious traditions represent the basic hopeful yearning of even the most jaded and downtrodden people, and using Muslim allegory to argue for peace in the Middle East, as Cairo rather blatantly does, is a very effective way of breaking through entrenched emotional resistance to the ideas of peace and humanity Wilson espouses. These sections are some of the strongest in the book.

A previous reviewer commented that "Wilson's talent as a writer and an agent of change cannot be denied." I'm in complete agreement about her literary talent, but I'm not so sure about the "agent of change" part. While I hesitate even to make this criticism given how much Wilson has risked by even discussing these issues openly, I think Cairo is not pitched correctly to move recalcitrant hearts and minds in the Middle East. Wilson's discussion of the destructiveness of conflict in the Middle East is imbued with the eager preachiness of youth, a flaw I too often find in my own writing -- we young people want to state our truths too directly, without realizing that the skeptics have heard it all before and require a fresh portrayal. Wilson needs to develop a language like that used by Orwell in Animal Farm, where the allegories and allusions of the story show the message without need for the editorial comment she so greatly overuses in the later sections of the book.

Perhaps more importantly, readers who sympathize with the more extreme camps on either side of the Israel question -- whom polls show are the majority in both Israel and Palestine -- will not recognize themselves in any of the characters. Tova, the Israeli soldier, takes a principled stand against the Israeli settlements in the West Bank; none of the Muslim characters has any interest in eradicating Israel from the map, with the exception of the American wannabe suicide bomber, Shaheed, who comes off as an idealistic outsider rather than a native embittered by a lifetime of coexistence with the Israeli army. There's little attempt in this book to integrate Hizballah or Likud supporters into the happy picture of harmony, yet those are the people who drive the debate and control the levers of power in the region. It's relatively easy to show how moderate Arabs and Israelis can solve the problems of the Middle East, but I would have liked to see Wilson draw on her unique experience as a former resident to try to humanize the extremists and show a path for them, too, to find peace.

Again, I've been harsh in these critiques in an effort to be constructive, not to condemn the book in any way. Cairo is an excellent first effort by Wilson, who is clearly someone to keep an eye on in the future, and is a delightful and meaningful read that will leave you contemplating the characters and the story, as I have been, for days after you finish it. You'll be left wanting more reading material by this young author, who will, I think, swiftly develop into one of the major writers of her generation on Middle Eastern issues.

Labels: Jeremy Young

" as a moderate supporter of Israel politically, I didn't expect to enjoy characters like Ashraf and his friend Ali, a Caironese alternative newspaper publisher, as much as I did"

um...what exactly is the "political" hindrance to enjoying "aesthetic" creations such as Ashraf or Ali? Are people who are politically critical of Israel barred from enjoying Etgar Keret?

The comic book sounds intriguing, nonetheless.

manan

Unknown on 12/03/2007 4:05 PM:

Ahistoricality, as an ethnic half-Jew myself, I'm sure you're right, but let me put it this way: I could tell what kind of features Perker was trying to get at, and I don't think he succeeded. Sorry for the Potter Stewart defense ("I know it when I see it"), but I think it eliminates some of the language you, probably rightly, found troubling.

Manan, I knew (from reading Willow's blog) that the book had a distinct political point of view and portrayed Arabs as the main characters. As a supporter of Israel, I expected to find the Arab characters portrayed in a manner I found uncomfortable -- in a way that indicated that their point of view was somehow superior to that of Israelis, for instance. That didn't happen.

Sounds interesting, but limited. I'm struck by some of the "exotic" language you use, though, which makes me nervous about the whole thing. e.g.:

his attempt at rendering ethnically Jewish features often makes the character look ugly rather than distinctive.

There are several (at minimum) distinct "Jewish" phenotypes (which really aren't Jewish at all, but which do occur with great frequency within the Jewish community) which could be taken as marking distinct subgroups within the community, groups with complex inner relationships and class-like relations. The tendency of Arabs to highlight the Eastern European Ashkenazi as typical vs. the European tendency to see the Sephardic/Mizrahi line as typical, for example, raises difficult questions about "othering"....