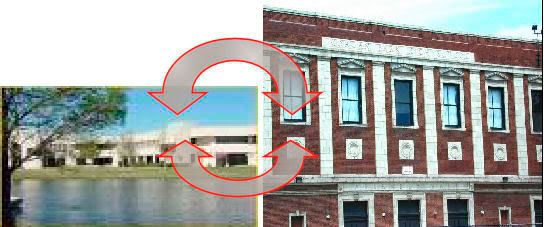

Two schools. Plano, Texas. Chicago's Morgan Park. Suburban. Inner city. Rich. Poor. White. Black. High-performing. Struggling.What if somehow you could switch the students? Would their performance improve? The answer will surprise you. Read on.

Not surprisingly, everyone is afraid of the obvious solution--putting Morgan Park's students in Plano. No city, community, state or the federal government has ever proposed a widespread integration plan that involves equalizing enrollments between the inner cities and the suburbs. No politician has even hinted at such a plan. Why? Because the real political dynamite behind this has to do with the elephant in the room, which is that no suburbanite wants their child to be forced to attend an inner city school because they KNOW inner city schools are inferior. Add Hollywood's image of the inner city along with a large dash of racism and you have a potent recipe for the political equivalent of nitroglycerine.

Since it won't happen in reality--at least not in the next few years--I propose one of Einstein's famous thought experiments. Imagine transporting every Morgan Park student to Plano?

If you traded schools--even for a week--the Plano students might realize how really lucky they are and the Morgan Park students would have their eyes opened to a new world. So, as a start I dare some suburban district to trade their students with those in an inner city school for even a day or two days. Not just a group of visitors, though, but the entire student body, every single one of them.

The gnawing question is if you could continue this experiment for six months, a year, even four years, would Morgan Park's students perform as well as Plano's? Would they have 81% scoring three or better on the advanced placement tests? Would there be a blossoming of National Merit Scholarship finalists?

Flight Simulators

At this point the thought experiment seems to fall apart, because in most people's minds any answer would be purely speculative. However, school decision makers have always dreamed of a tantalizing possibility: What if you could try out an initiative before you had to implement it? What if you had a process that went beyond focus groups, committees, and even pilot projects and could simulate the possible effect of an initiative on the system?

There actually exists a way to do this that has been used by a who's who of major international corporations. The process is called System Dynamics and has been in use for several decades since its creation by MIT professor emeritus Jay Forrester. Popularized by Peter Senge in The Fifth Discipline, The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook, and Schools That Learn, System Dynamics mathematically models the components of a system to better understand how they interact, allowing you to take apart and rebuild a system as if it were a Lego creation, relieving you of having to experiment on real students or teachers. It parallels the simulators used by pilots and others to train for potentially life-threatening situations.

So we can simulate what would happen to Morgan Park's students in Plano. Think of it as an educational version of SimCity. So where do you start? Actually Einstein himself had the answer to this and it comes down to one word: time. Only instead of hearing it from Einstein, I heard it from a brilliant University of Minnesota professor and researcher named Mark Davison, who pointed it out to me when I was head of a national school reform group. A mild-mannered person with the kind of self-effacing manner that sometimes comes with those who think deep thoughts, Davison is an internationally-recognized statistician.

On a hot July afternoon in a deserted classroom, Mark explained to a group of us over the hum of the fans how much of the data he had collected as head of the Office of Educational Accountability showed time to be a crucial factor in boosting student achievement. Over the next four years, our group explored Davison's idea. Since you obviously could not go into a school and suddenly change everything, we built our own thought experiment--a System Dynamics model of a school like the models used by for corporate planning. I won't bore you with the details of this six-thousand equation, sixth-order feedback model other than to say its accuracy proved uncanny.

As we discussed the role of time in the system with others, we found teachers and administrators immediately resonated with it. Juan or Juanita takes a certain amount of time to learn a lesson--and that varies by subject, learning philosophy and even the day of the week. I once joked to Jay Forrester that I would never learn math as quickly as he did and he smiled and nodded in agreement.

In addition, as all teachers know, a student may breeze through assignments, but may have a tendency to disrupt the class. Behavior plus how much time it takes different students to learn different skills and subjects equals what we called total classroom learning demand.

In a classroom, each teacher has a certain amount of time to give each student, with experience and talent governing how efficiently they use it. Administrators, aides, staff, supplies and facilities influence this efficiency. We called this classroom resources.

Learning, then, can be seen as a variation on the classic supply-demand equation: how much demand do the students bring, how much in the way of resources does the system have to meet these time demands? In this sense everything in the system contributes to the time available for students.

If a district has high student demands, but low resources, you have fractional performance. On the other hand, if resources are high, a district can handle a great deal of demand.

Feedback Loops and Tipping Points

The biggest impact of focusing on time is to completely change the mindsets of those working with inner city schools. The problems of inner city schools have nothing to do with the failings of students, teachers, administrators, or the community. They have to do with the simple fact that we are not giving these students enough time. As Peter Senge has told me on numerous occasions, it is not about people, it's about the system.

You can see how this alters so many of the assumptions we have about schools. For example, much is made of class size, but you can have an extremely small class full of high demand students and an inexperienced teacher and end up with a disaster. To show how this works, let's take the highly publicized Gates Foundation smaller schools initiative. Without any of these data, the initiative is essentially worthless. If we don't know the relative demand of the students or the resources of the teachers then we have no idea why the effort might be succeeding in one school and not in another. Their so-called "small schools" could have high resources and low demand and look great.

The point of this is that failings of the system are neither the student's fault nor the teachers. Now before some wingnut jumps in and says students are responsible for their behavior, I will jump in and say, in principle, of course they are. But the system must deal with reality not ideology. This also illustrates a basic fact about education: either you believe students are capable and want to learn or you believe they are inherently stupid and must be forced to learn. Republicans seem to fall into the latter group.

Much so-called "acting out" stems from students either being regarded as inferior or not being given enough time. We all know of the famous experiment where teachers are given false information about their students' abilities and character and treat them accordingly--with the result that students who may "really" be labeled as learning disabled are treated as if they were gifted, raising their test scores. As for time, not being given enough time is equivalent to being ignored. No one likes to be ignored so you either tune out completely or start to "act out."

There is also a feedback loop between school performance and student performance, especially with No Child Left Behind. Low performing schools are told something is wrong with them which in turn causes students to feel something is wrong with them or to react to the draconian measures employed to raise their test scores. Just think how you would feel if you were told your school was low performing? How do parents and the community feel?

As for the teachers, they can only handle so much demand based on their experience and training. To put them in a situation where the demand is too high is like handing someone a boulder and asking them to jump in the river. The result of this can be low teacher morale or teachers leaving the system completely.

Very few educators and no major policy makers have viewed inner city education from a systems perspective, focusing on interrelationships and their feedback loops. For example, if performance is low, teachers may become discouraged, lowering morale. Some will even quit or move to another school or even another district. This in turn further lowers performance. Students will pick up on this and tune out or act out even more, causing even more low morale.

Essentially many inner city schools are caught in this spiral, which if serious enough results in what systems thinkers refer to as a "death spiral" for the system. A "death spiral" occurs when the resulting feedbacks multiply geometrically, making it impossible to pull out of the decline like an airplane plummeting to its doom. The point of no return is referred to as the "tipping point," which comes from old pilot's and flight simulator lingo for when the nose of a plane has tipped so far no pilot can pull it out of its stall. For corporations and others, models have proven invaluable in identifying these tipping points, just like the gauges on a plane.

Two Schools: Plano and Morgan Park

Focusing on students and teachers provides an excellent perspective on the differences between Plano and Morgan Park. To their credit both Texas and Illinois collect good data on their schools, unlike my own home state, Minnesota, which has all but hidden data that used to be readily available.

Start with the teaching staff. Both schools are relatively close in terms of overall teacher experience, with Plano's average being 13.5 and Morgan Park's 13. Texas keeps a bit better data about how this breaks down, with one quarter of their teachers having over 20 years' experience, as compared with a district average of 15% and a state average of 19%. This is typical of high-performing schools, because due to the seniority rules that govern teachers' unions, teachers with high seniority can "bid" on open jobs in these schools and snag them. Think of this as another feedback loop. We have already seen that over 70% of Plano's teachers hold advanced degrees--something that also comes with both seniority and high performance, because teachers with advanced degrees hold higher positions on the "steps and lanes" systems that govern salaries and other teaching factors.

Morgan Park's data does not break down the years experience into groupings, so you have no idea of knowing if the teacher experience average is due to high numbers at both ends or high numbers in the middle. What we do know about Morgan Park is that its teaching force contains 2% of teachers who have emergency credentials and that 8% of its classes are taught by teachers who are not highly qualified, which in education is often a euphemism for teachers teaching "out of subject" such as a social studies teacher teaching English. This tends to happen often in advanced subjects mainly because there are no teachers to teach them.

Morgan Park's teaching data also shows an ominous development over time which reinforces that feedback loop. The average years of experience has dropped two years since 2000. In terms of its overall teaching force, Morgan Park's is about average for Illinois, while Plano's is above average for Texas and its district.

It is with the students we begin to see real differences. Here it is important that we suspend racial stereotypes and deal with the data. As we have seen, Morgan Park is now 92% African American, which is up dramatically from 76% in 1999--a statistic which tells a great deal about the impact of educational apartheid. Fifty-eight percent of Morgan Park's students are low income. A distinguished educational researcher has told me one major predictor of school performance is the number of students on free lunch--not because they are poor, but because they obviously have poor nutrition which has an impact on learning. Morgan Park also has a mobility factor of 10%, a truancy rate of 9% (which by the way has TRIPLED since 1999), a dropout rate of 3.6% and a graduation rate of 85%. According to the the school profile compiled by the Chicago Public School System, 13% of Morgan Park students have disabilities.

Compared to Morgan Park, Plano has a mobility rate of 9%, a dropout rate of .4% and a graduation rate of 92%. Only 8.6% of Plano's students are classified as "economically disadvantaged," which is not surprising considering the town's annual income of $96,000. Texas reports only 1.2% of Plan's students received disciplinary placements. Illinois does not keep these data.

Just looking at the data from both schools you can see if you ran the numbers in a simulator or even in the equation, Morgan Park would be hard-pressed to have a high resource/demand ratio while Plano's will be quite high. Not surprisingly according to No Child Left Behind classifications, Morgan Park is listed as not making adequate yearly progress while Plano is a "recognized" school. Nothing better illustrates what educational apartheid has done to our country.

Raising Achievement

So what would it take to raise achievement in Morgan Park? In simple terms it means balancing the equation which means more teachers--especially more experienced teachers--to meet the demand. Instead the school appears to be fighting to hold its own. While those passing the reading test has stayed flat at 70%, mathematics performance has steadily improved from 54% to 62%. On the other hand those "above standard" in math have declined 20% and, more ominously, 20% score below standard in writing. It is important to remember all those feedback loops and their systemic impact. In System Dynamics terms, Morgan Park is a school near the "tipping point," that without an infusion of resources will be in serious trouble. Little wonder that only 28% of Morgan Park's parents report "satisfaction with the school."

Although the supply/demand equation may seem simple and the solution of adding more staff to Morgan Park obvious, it is important to understand it from a nonlinear, System Dynamics perspective. It almost requires changing the way you look at the world, which is not an easy thing to do. Since learning System Dynamics, I find myself coming from a very different place than many people. Imagine, then instead of an equation, a diagram with arrows representing feedbacks around the elements.

Then you begin to see how what seemed a simple policy issue can become a great deal more complex. This is where Jay Forrester's famous Law of Unintended Consequences comes into play, because in a SYSTEMS WORLD any change you make in one part of the system rebounds through those feedback loops. The result can be that if you don't understand the system, you can actually make it worse. Which is why modeling becomes so important. I have heard Jay Forrester say one of the reasons we need tools like System Dynamics is that systems have become so complicated with so many variables that it is beyond the capability of a single mind to handle them.

For example, take more teachers. They will create a demand for more space and more teaching resources. More administrators and support staff are needed to work with them. If they are new to the school, they need intensive staff development and/or existing teachers must mentor them--of course, taking time away from their own work.

The Cost of Apartheid

The result is that the cost of improving inner city education is not linear--the proverbial upwardly angled straight line that is shown in Morgan Park's improvement plan, but a curve that grows steeper the closer the school moves to close the gap, since those whose scores change first demand fewer resources. Years ago we actually modeled the costs of improvement for an inner city district. The answer was not one policy makers wanted to hear. That district was spending about $10,000 per student, but by the time you factored in all the above factors and feedbacks related to raising this district's performance to 90% passing on the state test--which is roughly equivalent to moving Morgan Park's students to Plano's level--the cost was over $50,000 per pupil!

This number is an indication of what educational apartheid has cost our country! Morgan Park is so far behind Plano that it could take as much as $20,000 to $50,000 per student to catch up--and that doesn't factor in the facilities! We are not just separate but unequal, but separate and unjust. Probably at this point, there are those who would argue that cost prohibits our remedying educational apartheid. That is probably the most inequitable, despicable decision this country could make.

Let me interject here that we have not even taken into account the deplorable condition of many inner city schools. In fact it reinforces the need to improve them because inadequate facilities add to the time demand side of the equation because they make ANY learning difficult. If you continue to have lousy facilities, multiply those time demands by a factor of two or more depending on how bad they are. If the Plano students and faculty could actually spend a week in Morgan Park, they would see this immediately. Suddenly what seemed easy and efficient becomes time-consuming and inefficient. Students take more time getting to class or even using the bathrooms. The Plano teachers also would miss all the resources that add fun and individualization to learning.

It All Comes Down to Principles (and Principals)

The bottom line of educational apartheid is as clear as the resource/demand equation. More than anything time provides an answer to the apartheid question. Give inner city students the TIME they DESERVE and their performance will improve. I can guarantee it. Yet, before embarking on yet another massive federal effort, we must first agree on the principles that will guide it.

First, like South Africa, America needs to acknowledge its guilt for educational apartheid and deal with it. There is little question we need a national effort akin to the one we made when we feared Sputnik signified the Russians were way ahead of us, only now it's not a Cold War but educational apartheid. In March and April of 1958, Life magazine published an unprecedented five-part series about the need to mobilize America's education resources. That same year Congress passed the billion dollar National Defense Education Act. It will take at least the contemporary equivalent of that to solve the apartheid problem.

Second, even if we did spend $50,000 per pupil that might satisfy the current Supreme Court and those racists who would just as soon their children not sit next to children of color, but it fails to satisfy the basic principles of this democracy. Among those is the idea that whatever we do must be lead by the people in the local community. Virtually every education reform effort in the inner city has been done TO people rather than with them. People in the inner city not only know what will work, but should control the effort and involve their communities, which would help alleviate the time issue. There are scores of programs out there, but no one has said to an inner city community: which one would YOU like.

The third principle is that we need to involve the students. Years ago I proposed a health care initiative that essentially focused on primary care by getting students involved in delivering care and then paying for their health education in exchange for agreeing to come back and serve in their communities. One solution to the time problem is to use students as a resource rather than a demand. In multi-aged classrooms students help one another. They could do that at Morgan Park.

Fourth, is the principle that the people of the inner city deserve the best we can give them and that means all our actions should be guided by the latest research, use the latest learning technologies and, above all, be based upon a systemic approach. Otherwise everything we do will risk the Law of Unintended Consequences. That means using twenty-first century tools like System Dynamics.

Finally, I will play my last card here and say I believe that nations, like ecosystems and species survive through diversity, not uniformity. A true level playing field is a diverse one, for if someone is excluded then by definition the playing field is not level. So many achievements the world identifies as uniquely American, such as our popular music and art, have come from the cross-fertilization--and yes, even the clash--of cultures. When people and communities are free to be who they are and who they want to be and these differences are given opportunities to interact, the amazing happens.

The fundamental assumption behind this series has been about the need to open our minds to possibilities, not to close them. This last part, especially, has asked readers to adopt what amounts to a new pair of glasses through which to see reality. My friend Lew Rhodes, who used to be in the national office of the American Association for School Administrators, likens it to the change in perspective Galileo's telescope brought to the world. Yet behind these new glasses--as hard as they have been to see through--lies an important truth about equity, in education and in America. Without true equality and the diversity it encourages, fresh voices will die within the concrete cave-like walls of some inner city school. An Ida Wells, a W.E.B. DuBois, a Wynton Marsalis, a Tiger Woods will perish and we won't even know it.

In my favorite chapter of the book The Strange Death of Liberal America, I wrote about Fannie Lou Hamer, who learned to tutor herself like slaves in the nineteenth century, by reading books in the plantation owner's house when she was asked to "sit" with sick people. As we know, Hamer went on to become one of the outstanding leaders of the last century. She is one of those rare people of whom you can say, without her, America would not be America.

That this genius came from a woman who tutored herself like many others have been forced to do, demonstrates a fundamental liberal principle: a level playing field will produce uncommon people, because you never know when someone like Hamer will seize the tattered threads they have been given and weave them into something singular.

Fannie Lou Hamer reminds us that educational apartheid--whether separate but equal or separate but unequal--is the ultimate demand unit, for it makes true learning impossible. There is only one future for a nation practicing educational apartheid. Extinction. Like the dodo bird and the dinosaur America will become extinct, because lacking diversity it will be unable to respond to change. In this global economy that will happen sooner, rather than later. The question is not if, but when.

We also should remember that the conditions of educational apartheid are far more serious and volatile than the foreign terrorist bogeymen that keep Americans awake at night and bloggers clogging our bandwidth. Educational apartheid gave birth to the terrorists we now fear, for they were nurtured in schools that purposely shut out diversity. Instead of worrying about al Qaeda we should worry about Al and Allison growing up in the inner city. Instead of worrying about people flying planes into buildings, we need to worry about people driving millions of students into unsafe schools that are waiting to explode.

Like many of my projects this began with a simple question about equity. In the end it comes down to that. This series is dedicated to the people of America's inner city schools. It has been long and detailed, and at times even a bit challenging, but America's inner cities deserve an open and extensive airing of their problems. They deserve the best I can give them, which means not cutting corners. My hope is that perhaps those who have read this series have been enlightened and inspired. If what Thomas Jefferson saw as the foundation of democracy is not for ALL of us, then we do not deserve to be called a democracy.

Crossposts: NION, My Left Wing, The Strange Death of Liberal America

.Labels: Ralph Brauer

Ralph Brauer on 11/10/2007 4:10 PM:

ABSOLUTELY! NCLB is an unfunded mandate, period. Unfortunately no one has the guts to confront this because if you do open the door to folks like me who can show what the costs would be.

Administrators I know tell me the cost of ADMINISTERING the test alone is probably worth the equivalent of one or more teachers depending on the size of the school. Even dismissing that administering the tests takes several days out of the school year. Our American schools--which BTW lag behind the rest of the world in terms of time spent on learning--are behind even where they were a few years ago just because administering and taking the tests has shortened the school year.

It gets more interesting from a systems perspective. IF you buy the model then the lower the scores the more time needed to be spent teaching to the test (which is what many urban schools are doing). It essence our schools become versions of Kaplan or those other test-preparation companies. Kaplan, in fact, is trying to get into this business beyond its usual reach. In schools where performance is so bad students are allowed to seek out other sources, Kaplan and other companies can bid on replacing the school.

Your point about the social costs is the point of the entire series.

Looking at your feedback loops and the immense cost of achieving parity (which is nothing compared to the long-term cost of disparity, but that's another discussion) I wonder whether we could achieve some savings by dropping NCLB altogether. Not that I wasn't in favor of it already, but it's one more piece of evidence on the scales....