by Gordon Taylor | 10/30/2007 11:46:00 PM

These days the online papers seem to be full of news about the PKK. It's as if the editors are saying, "Hey, send somebody up there and get a story." You can find a good sampling of the latest at Mizgin's blog, including one from the L.A. Times and another from the Sunday Times of London. The latter brings us the news that, lo and behold, there are several Britons in the ranks of the PKK army. The L.A. Times article informs us that, yes indeed, they are scattered across an extremely remote and inaccessible area. Mizgin has these and the translation of a statement by Murat Karayilan of the PKK on the condition of the 8 captured Turkish soldiers. (They're fine, he says. Basically, the PKK just wants to get rid of them; unfortunately the Turks keep shelling the mountains and keeping his men from getting them out. But then, the Turkish Army hasn't even admitted yet that the men are prisoners.) Meanwhile, in Istanbul, the pro-Kurdish newspaper Ozgur Gundem keeps getting knocked out of cyberspace by the Turkish authorities. Their sin: publishing news that people want to read about. It happens all the time.

I'm going to publish some more photos from the PKK website, but first I want readers to remember the obvious: if you're the parent of a Turkish soldier who has been drafted, sent to the East, and killed in a firefight with the PKK, you have good reason not to like these people. War is hell, on both sides, and both sides have endured their share of grief. Pretty pictures should not blind us to that reality. As for the PKK themselves, we'll have plenty of pictures to show later.

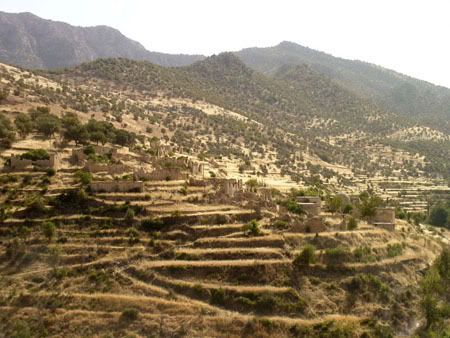

Actually, the photograph above was not taken by the PKK. I took it in May 1977. It shows the village of Kespiyanish, inhabited by Kurds and now branded by Turkish bureaucrats as Mutluca, or the happy little place. Kespiyanish used to be inhabited by Nestorian Christians. They were driven out during the First World War. The church they built still stands, a testament to the skill they put into the stonework. All mountain churches are entered through a porthole-like opening, requiring the visitor to step over a knee-high threshold and duck his head. This has effectively kept the Kurds from making any use of the structure. The Kurds of Kespiyanish were convinced that the Christians had buried gold on the premises, and nothing I said could dissuade them from this. Actually, the gold is elsewhere:

This is where their gold really lay: in the Nestorians' terracing systems, intricately laid out and arduously maintained. Here they grew everything they needed. This is a PKK photo. I can't say for certain that it depicts a deserted Nestorian village. There are, after all, plenty of deserted Kurdish villages in the mountains. And travelers' accounts make it clear that, depending on which district they found themselves in, the Kurds too excelled in this type of agriculture. But travelers in the district of Hakkari (now in Turkey) point out that in one particular tribal area (Tiyari) the Christians were so feared, and held in such dread by the Kurds, that they felt secure enough to keep their houses spread out and close to their fields. Usually, it is otherwise: mountain village houses are always bunched together, stacked one on top of another, as a means of gaining security. More like this:

Again, I have no idea where this village is, but it's probably in Turkey. Note the sharpness of those right angles in the stonework. Again, it's a feature that varies from district to district. I've seen Kurdish stone dwellings in Mardin that were superb; elsewhere, the walls are stacks of rough stone mortared together with mud, then roofed over with branches and more mud on top of that.

This is more like it. This gives us a feeling of the immensity of it all, of a place where you can stand upon snow and look off onto the plains of Mesopotamia, and temperatures well over 100 degrees. It's the guerrillas' world, and here is their rations:

This is the classic peasant meal in Turkey: a beaten shield of metal, a fire, and the simplest bread possible. Bun and Run. But there are a few compensations:

On April 26, 1849, Justin Perkins, an American missionary from Amherst, Massachusetts, wrote in his journal from the Kurdish mountains: "Another villager brought us the finest flower I ever beheld, which he had picked, in its wildness, on the neighboring mountains." He then went on to describe the flower shown above. In gardening circles it is called the Crown Imperial fritillaria, and it grows (from a bulb) to a height of 3-4 feet. In Turkish it is called the "ters lale," or "inside-out tulip," and it is a protected species in the mountains of Hakkari province. The PKK women like them, too, as this photo shows:

And what would a survey of the flora be without this?

These are, please take note, the real deal: genuine wild tulips blooming in the place where the species originated. In a way, the tulipomania of Holland (its genes, at least) can be traced back to here.

But it's scenes like the following that we need to think of when the war comes:

Hidden torrents; brush-covered canyons; waterfalls:

With only occasional aids to navigation:

Next time, I believe, it's time to start looking at people:

That, as we'll see, will contain some big surprises.

Labels: Gordon Taylor

I have been meaning to tell you how much I have enjoyed this series, which is only enhanced by the photographs. Most of all I am beginning to feel I know these people because of your outstanding work.

To me this is what blogging is for and all about: a place where you can find information the mainstream media keep from us.

I look forward to the next post!